International Monetary Fund | April 2023 91

Supply-chain disruptions and rising geopolitical tensions

have brought the risks and potential benefits and costs

of geoeconomic fragmentation to the center of the policy

debate. This chapter studies how such fragmentation can

reshape the geography of foreign direct investment (FDI)

and, in turn, how FDI fragmentation can affect the

global economy. The recent slowdown in FDI has been

characterized by divergent patterns across host countries,

with flows increasingly concentrated among geopolitically

aligned countries, particularly in strategic sectors. Several

emerging market and developing economies are highly

vulnerable to FDI relocation, given their reliance on FDI

from geopolitically distant countries. In the long term,

FDI fragmentation arising from the emergence of geopolit-

ical blocs can generate large output losses. These losses may

be especially severe for emerging market and developing

economies facing heightened restrictions from advanced

economies, which are their major sources of FDI. Mul-

tilateral efforts to preserve global integration are the best

way to reduce the large and widespread economic costs of

FDI fragmentation. When multilateral agreements are not

feasible, multilateral consultations and processes to miti-

gate the spillover effects of unilateral policies are required.

In a more fragmented world, some countries could reduce

their vulnerability by promoting private sector develop-

ment, while others could take advantage of the diversion

of investment flows to attract new FDI by undertak-

ing structural reforms and improving infrastructure.

Introduction

Rising geopolitical tensions and the uneven distri-

bution of the gains from globalization have contrib-

uted to increasing skepticism toward multilateralism

and to the growing appeal of inward-looking policies

(Colantone and Stanig 2018; Rodrik 2018; Autor

e authors of this chapter are JaeBin Ahn, Benjamin Carton,

Ashique Habib, Davide Malacrino, Dirk Muir, and Andrea

Presbitero, under the guidance of Shekhar Aiyar, and with support

from Shan Chen, Youyou Huang, Carlos Morales, Chao Wang, and

Ilse Peirtsegaele. e chapter benefited from comments by Richard

Baldwin and seminar participants and reviewers. Eswar Prasad was a

consultant for the project.

and others 2020; Pastor and Veronesi 2021). Brexit,

trade tensions between the US and China, and Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine pose a challenge to international

relations and could lead to policy-driven reversal of

global economic integration, a process referred to as

geoeconomic fragmentation. is process encom-

passes different channels, including trade, capital,

and migration flows.

1

is chapter focuses on one

specific channel—the fragmentation of foreign direct

investment (FDI), which is cross-border investment

through which foreign investors establish a stable and

long-lasting influence over domestic enterprises.

A slowdown in globalization—often referred to as

“slowbalization”—is not new. For most countries it

dates to the aftermath of the global financial crisis

(Antràs 2021; Baldwin 2022). A decrease in FDI has

been particularly visible, with global FDI declining

from 3.3 percent of GDP in the 2000s to 1.3 percent

between 2018 and 2022 (Figure 4.1; see also

UNCTAD 2022 for an overview of recent trends in

FDI). While a range of factors have contributed to this

protracted phase of slowbalization, the fragmentation

of capital flows along geopolitical fault lines and the

potential emergence of regional geopolitical blocs are

novel elements that could have large negative spillovers

to the global economy.

Firms and policymakers are increasingly looking at

strategies for moving production processes to trusted

countries with aligned political preferences to make

supply chains less vulnerable to geopolitical tensions.

2

1

Aiyar and others (2023) present signs of geoeconomic fragmen-

tation along different dimensions (for example, trade, capital flows,

and reassessments of geopolitical risk), analyze several channels

through which such fragmentation could propagate through the

global economy, and discuss how the rules-based multilateral system

must adapt to the changing world. See the April 2023 Global

Financial Stability Report for an analysis of the effects of geoeco-

nomic fragmentation on non-FDI flows, with implications for

financial stability and macro volatility.

2

e term “reshoring” refers to a country’s transfer of (part of the)

global supply chain back home (or geographically closer to home in

the case of “nearshoring”). “Friend-shoring” limits supply-chain net-

works and the sourcing of inputs to countries allied with the home

country and trusted partners that share similar values. e chapter

uses these terms in relation to the decision to relocate FDI (rather

than to the more general decision of where to source inputs).

CHAPTER

4

GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

92 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

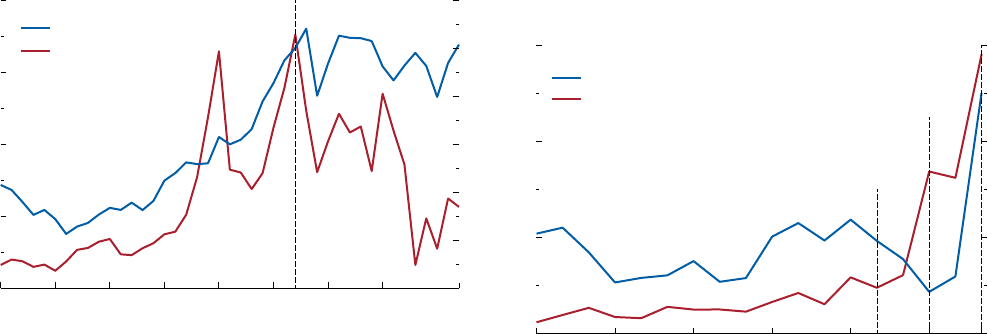

A text-mining analysis of earnings call reports from

a large sample of multinational corporations shows

a sharp spike in firms’ interest in reshoring and

friend-shoring (Figure 4.2), occurring at the same time

that the average geopolitical distance across country

pairs started increasing. Recently, US Treasury Sec-

retary Janet Yellen (2022) argued that rather than

relying heavily on countries with which the US has

geopolitical tensions, US firms should move toward

friend-shoring of supply chains to a large number of

trusted countries. In Europe, the French government

has been urging the EU to accelerate production

targets, weaken state aid rules, and develop a “Made

in Europe” strategy to counter domestic production

subsidies provided by the US Inflation Reduction Act

(Tamma and Stolton 2023). In China, too, govern-

ment directives aim to replace imported technology

with local alternatives to reduce dependence on geo-

political rivals (Bloomberg News 2022). Rising interest

in reshoring is a significant reversal of the division

of production pursued through offshoring, driven

predominantly by differences in labor and input costs

(Feenstra 1998; Antràs and Yeaple 2014).

e importance of friend-shoring goes

beyond just announcements and translates into

investment-screening measures motivated by national

security purposes (UNCTAD 2023). Recent large-scale

policies implemented by major countries to strengthen

domestic strategic manufacturing sectors suggest

that a shift in cross-border capital flows is about to

take place. Most notable is a series of recent bills

adopted against the backdrop of rising US-China trade

tensions—such as the Creating Helpful Incentives to

Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) and Science Act

and the Inflation Reduction Act in the US and the

European Chips Act—that could affect multinational

corporations’ production and sourcing strategies,

prompting efforts to reconfigure their supply-chain

networks (Box 4.1).

is reconfiguration of supply chains could poten-

tially strengthen domestic security and help maintain a

technological advantage. It may also increase diver-

sification, provided the existing supply of inputs is

concentrated in a single or a small number of foreign

suppliers, such that domestic and close-country sourc-

ing would increase the number of available options.

However, as most countries exhibit a marked degree

of home bias in sourcing of inputs (see Chapter 4 of

the April 2022 World Economic Outlook), in most cases

reshoring or friend-shoring to existing partners will

likely reduce diversification and make countries more

vulnerable to macroeconomic shocks.

is chapter studies how geoeconomic fragmenta-

tion could affect the global economy through a shift

in the geographic footprint of FDI. While a grow-

ing literature investigates the costs of geoeconomic

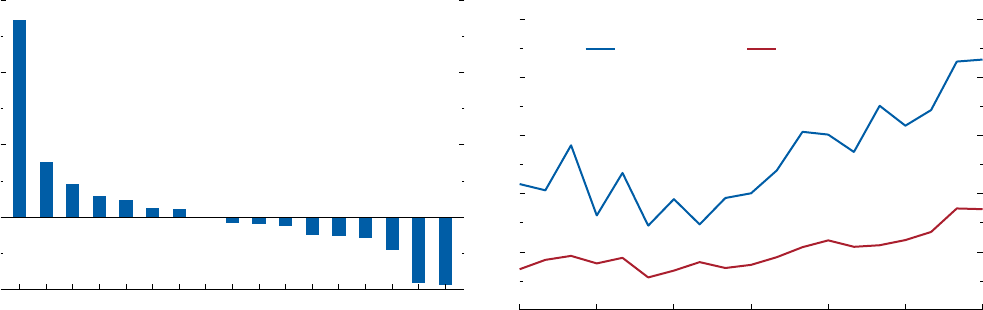

Trade in goods and services

Gross foreign direct

investment (right scale)

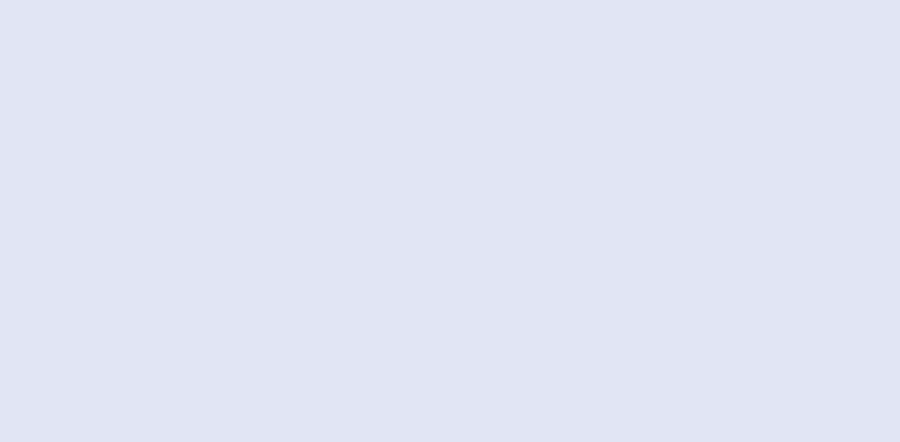

Figure 4.1. “Slowbalization”

(Percent of GDP)

Foreign direct investment sharply declined after the global financial crisis.

Global

financial

crisis

1980 85 90 95 2000 05 10 15 22

25

35

45

55

65

0

1

3

2

4

5

6

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Geopolitical risk (annual average, 1985–2019 = 100)

Interest in reshoring (right scale)

US-China

trade war

COVID-19

Ukraine

war

Figure 4.2. Rising Geopolitical Tensions and Foreign Direct

Investment Fragmentation

(Index; frequency of mentions of reshoring on right scale)

Recent years have seen increasing geopolitical risk and companies’ interest in

reshoring and friend-shoring.

2005 08 11 14 17 20 22

60

100

140

180

0

3

6

9

Sources: Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); Hassan and others (2019); NL

Analytics; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: The interest in reshoring measures the frequency of mentions of reshoring,

friend-shoring, or near-shoring in firms’ earnings calls.

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

93International Monetary Fund | April 2023

fragmentation through trade and technological

decoupling,

3

existing work has not yet looked directly

at FDI fragmentation. But this is likely to be a relevant

channel through which the emergence of geopolit-

ical blocs could have global spillovers. In fact, FDI

accounts for a substantial share of domestic capital

stock globally—about 12 percent, on average—and is

generally associated with knowledge transfer to domes-

tic firms and economic growth, especially in emerging

market and developing economies (Alfaro and others

2004; Javorcik 2004; Kose and others 2009). A reloca-

tion of FDI closer to source countries could have direct

negative effects on current host economies through

lower capital and technological deepening, as firms

expressing interest in reshoring and friend-shoring

tend to be on average larger, more profitable, and more

knowledge-intensive (Figure 4.3).

Against this backdrop, this chapter starts by looking

for early signs of FDI fragmentation, using detailed

bilateral investment-level data on FDI from 2003

to the end of 2022. It investigates two questions:

(1) Is there any evidence of reallocation of FDI across

countries, indicating that flows are becoming more

fragmented? and (2) Do geopolitical factors contribute

to explaining bilateral FDI flows, so that countries

deepen their integration with friends and reduce

their reliance on foes? e chapter develops a multi-

dimensional index of countries’ vulnerability to FDI

relocation combining information on the geopolitical

distance between source and host countries, share of

strategic sector investment in total FDI inflows, and

degree of market power enjoyed by the host country.

Next, the chapter turns to quantifying the potential

costs of FDI fragmentation and their distribution across

countries. To understand the channels through which a

potential unwinding of FDI could affect host coun-

tries, the chapter empirically examines FDI spillovers,

taking both macro- and micro-level approaches. An

extensive literature on the economic effects of FDI on

host countries does not deliver consistent results when

simply looking at aggregate flows (Bénétrix, Pallan, and

Panizza 2022). e chapter extends this literature by

conducting a country-level analysis of the relationship

between GDP growth and FDI separately for horizontal

3

See, among others, Cerdeiro and others (2021); Eppinger and

others (2021); Felbermayr, Mahlkow, and Sandkamp (2022);

Giammetti and others (2022); Góes and Bekkers (2022); and Javorcik

and others (2022). A related literature looks at the effects of Brexit and

the 2018–19 US-China trade war; see Caliendo and Parro (2021) and

Fajgelbaum and Khandelwal (2022) for an extensive review.

and vertical investment, as the latter is more likely to be

affected by geoeconomic fragmentation. A subsequent

firm-level analysis combines investment-level FDI data

with a large sample of cross-country firm-level surveys

to identify potential spillovers to firm labor productivity

within and across sectors along the value chain.

Finally, the chapter calibrates a number of illustra-

tive hypothetical scenarios to provide a sense of the

possible long-term economic implications of FDI frag-

mentation using a multiregion dynamic stochastic gen-

eral equilibrium (DSGE) model. It employs scenarios

to explore the distribution of costs and benefits across

economies, including those from spillovers through

external demand and the reallocation of production

capacity. Fragmentation is modeled as a permanent rise

in investment barriers between opposing geopolitical

blocs centered on the two largest economies (China

and the US), with economies pursuing a nonaligned

path potentially facing heightened uncertainty.

e main conclusions from the chapter

are as follows:

• The recent slowdown in FDI has been character-

ized by divergent patterns across host countries,

particularly when considering investment in

strategic sectors, like semiconductors. FDI flows

are increasingly concentrated among countries that

are geopolitically aligned. The role of geopolitical

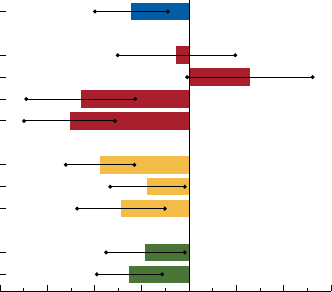

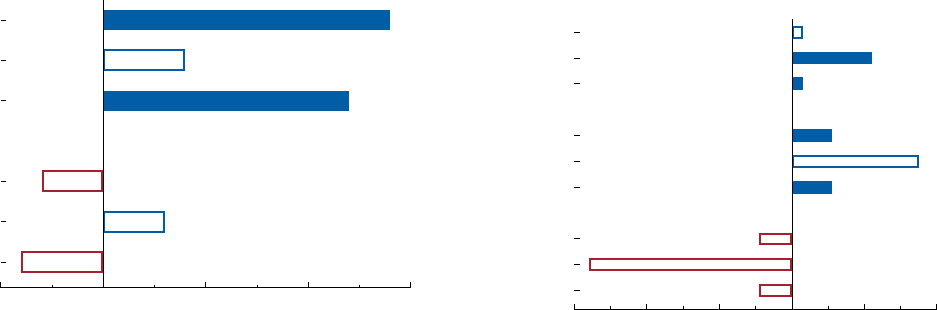

No mention of reshoring

With mention of reshoring

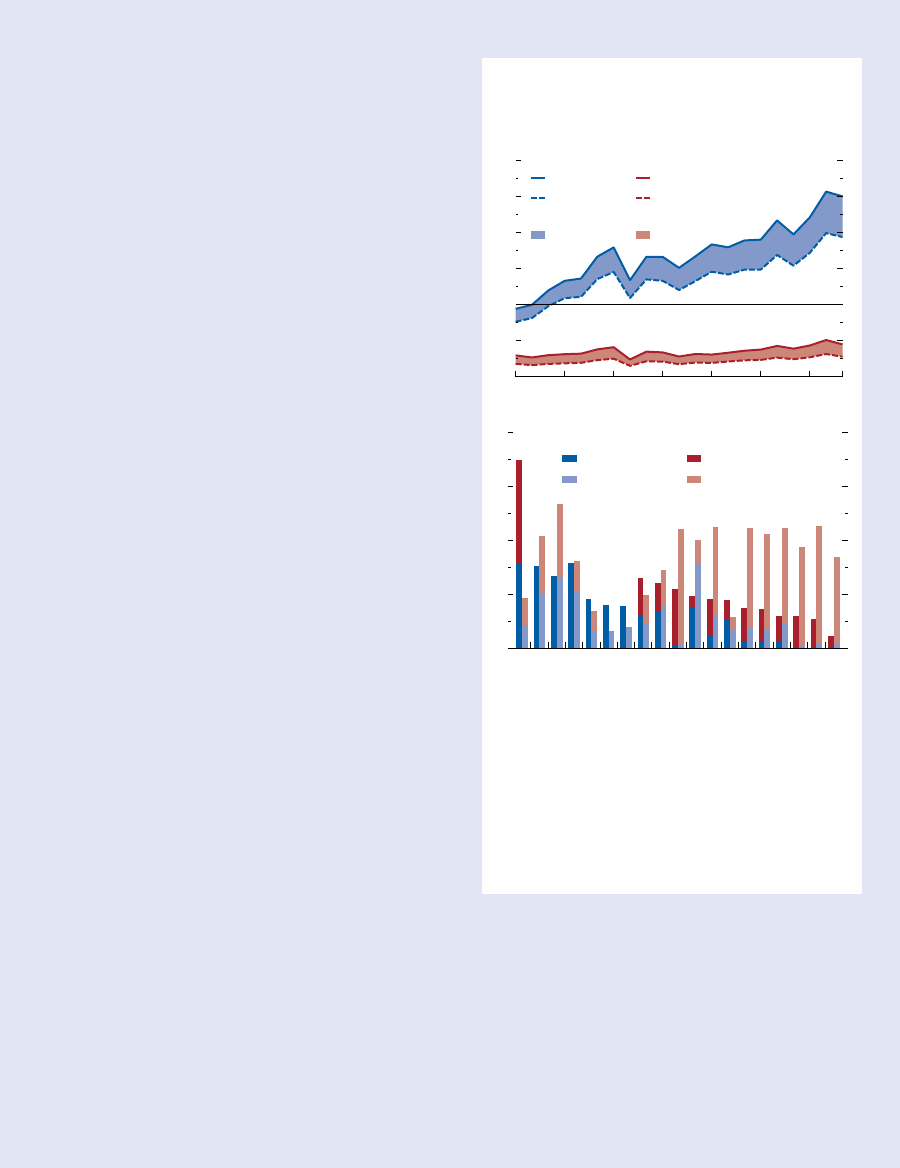

Figure 4.3. Interest in Reshoring and Firm Characteristics

Firms more likely to reshore are larger and more productive.

Number of

employees

Sales

(dollars, logarithm)

Intangible assets

(share of total

assets)

Profitability

(EBIT to assets)

–5

10

20

30

5

0

15

25

Sources: Compustat; Hassan and others (2019); NL Analytics; and IMF staff

calculations.

Note: Simple averages across firms that mentioned or did not mention reshoring,

friend-shoring, and near-shoring in earnings calls. Differences across groups are

statistically significant. EBIT = earnings before interest and taxes.

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

94 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

alignment in driving the geographic footprint of

FDI is particularly relevant for emerging market and

developing economies and has increased since 2018,

with the resurgence of trade tensions between the

US and China. Thus, if geopolitical tensions were

to increase and countries were to move farther apart

along geopolitical fault lines, FDI is likely to become

more concentrated within blocs of aligned countries.

Efforts to preserve a multilateral dialogue are needed

to keep FDI fragmentation from increasing.

• Analysis from a multidimensional index of vulner-

ability to FDI relocation suggests that, on average,

emerging market and developing economies are

more vulnerable to such relocation than advanced

economies. This is mostly because of emerging mar-

ket and developing economies’ reliance on FDI from

countries with which they are relatively unaligned

geopolitically. Several large emerging markets,

across different regions, show high vulnerabilities to

relocation of FDI, indicating that the fragmentation

scenario is not a risk only for a few countries. As

better regulatory quality is associated with lower

vulnerability, countries could mitigate their exposure

to FDI relocation by introducing policies and regu-

lations to promote private sector development.

• A further contraction in FDI and a shift in its geo-

graphic distribution would likely have large negative

effects on host countries, through lower capital accu-

mulation and technological deepening. The chapter

finds that vertical FDI, more likely to be targeted by

policies aimed at friend-shoring investment in strate-

gic sectors, is associated with economic growth, not

least because of its knowledge-intensive nature. The

entry of multinational corporations also directly bene-

fits domestic firms. In advanced economies, increased

competition from foreign firms pushes domestic firms

to become more productive. In emerging market and

developing economies, domestic suppliers benefit

from technology transfers and increased local demand

for inputs from foreign firms in downstream sectors.

• Illustrative model-based scenarios suggest that FDI

fragmentation—modeled as a permanent rise in

cross-bloc barriers to importing investment inputs—

could substantially reduce global output, by about

2 percent in the long term. Simulations of various

hypothetical scenarios suggest that the losses are

likely to be unevenly distributed, with emerging

market and developing economies with reduced

access to advanced economies particularly affected,

through both lower capital formation and reduced

productivity gains. While the diversion of invest-

ment inputs could allow some economies to gain,

such benefits could be significantly offset by spill-

overs from lower external demand. Alternate sce-

narios are used to highlight that nonaligned regions

could have some negotiating power vis-à-vis the

geopolitical blocs. However, uncertainty regarding

their alignment could restrict their ability to attract

investment. The estimated output losses highlight

the importance of carefully balancing the strategic

motivations behind reshoring and friend-shoring

against economic costs to the countries themselves

and to third parties, including through multilateral

consultations to reduce uncertainty for bystanders.

Early Signs of FDI Fragmentation

Recent trends point to the emergence of FDI fragmen-

tation. is chapter relies on investment-level data on

new (greenfield) FDI from fDi Markets, which provides

data on about 300,000 investments from the first quarter

of 2003 to the fourth quarter of 2022. e richness

of the data—which include information on the source

and host countries and on the sector and purpose of the

investment—allows for zooming in on specific regions,

country pairs, and industries.

4

It also permits classifica-

tion of certain sectors as “strategic”: those for which poli-

cymakers may be particularly interested in relocation due

to national and economic security interests.

5

roughout

the chapter, the number of greenfield foreign direct

investments is used as the measure of FDI.

6

4

As the data do not show divestment, the chapter studies the

geographic footprint of new direct investments. Once aggregated

at the host country–year level, the investment-level data are highly

correlated with gross FDI inflows, and the distributions of the two

show a large degree of overlap, as also shown by Toews and Vézina

(2022). As data on mergers and acquisitions are not available from

the same data source, the analysis is based exclusively on greenfield

investments. New (greenfield) investments are more numerous than

mergers and acquisitions, especially in emerging market and devel-

oping economies; are more highly correlated with aggregate data on

FDI; and are less frequently concentrated in tax havens. To mitigate

the risk that findings are affected by phantom FDI (Damgaard,

Elkjaer, and Johannesen 2019), the robustness of the analysis is

tested excluding FDI from and to international financial centers.

More details are discussed in Online Annex 4.1. All online annexes

are available at www .imf .org/ en/ Publications/ WEO.

5

e chapter defines strategic sectors at the three-digit industry

level. More details are discussed in Online Annex 4.1.

6

As investment values in the fDi Markets data set are often estimated,

the chapter’s main analysis relies on the number of investments; in the

chapter, a change in FDI refers to a change in the number of greenfield

foreign direct investments. Online Annex 4.1 shows that the main

results are robust to the use of investment values.

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

95International Monetary Fund | April 2023

Many factors likely contributed to the slowdown

in FDI before the pandemic, such as increasing

automation and other technological changes (Alonso

and others 2022). Yet some recent patterns point to

increased FDI fragmentation as geopolitical tensions

and inward-looking policies have gained importance.

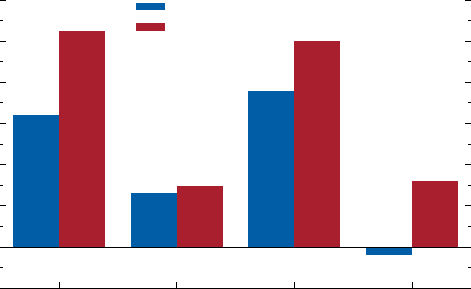

e flow of strategic FDI to Asian countries started

to decline in 2019 and has recovered only mildly

in recent quarters. By contrast, flows of strategic

investments to the US and Europe have proved more

resilient. As a result, by the fourth quarter of 2022,

a significant gap emerged between new investment

directed to these regions, with strategic FDI to Europe

about twice that going to Asian countries (Figure 4.4,

panel 1). Fragmentation—and specifically the lack of

recovery of FDI to China—is even more apparent for

foreign investment in R&D and in specific strate-

gic industries, such as the semiconductor industry

(Figure 4.4, panel 2), which both the US and the

European Union have targeted with policies directed at

strengthening domestic production and reducing the

vulnerability from unaligned foreign suppliers.

ese patterns are indicative of a more general

process of reallocation of FDI flows across countries.

FDI declined in the post-pandemic period from the

second quarter of 2020 to the fourth quarter of 2022 by

almost 20 percent compared to the post–global financial

crisis pre-pandemic average. But this decline has been

extremely uneven across regions, with the emergence of

relative winners and losers as both source and host of FDI

(Figure 4.5). Asia became less relevant both as a source

and host, losing market share vis-à-vis almost all other

regions. Notably, FDI to and from China declined by

even more than the Asian average, although the persistent

effect of the pandemic and prolonged lockdowns could

also have contributed to the fall in foreign investment.

In other regions, such as the US and emerging Europe,

greenfield FDI declined less and, in some cases, even

increased (for example, inflows to emerging Europe).

United States Europe

China Asia (excluding China)

US-China

trade war COVID-19

US-China

trade war

COVID-19

Ukraine

war

Ukraine

war

Figure 4.4. Foreign Direct Investment Fragmentation

(Number of investments, four-quarter moving average, 2015:Q1 = 100)

Foreign direct investment flows to different regions are diverging, with China

losing market share.

1. In Strategic Sectors

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2015:

Q1

17:Q1 19:Q1 21:Q1 22:

Q4

2. In Semiconductor Industry

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2015:

Q1

17:Q1 19:Q1 21:Q1 22:

Q4

Sources: fDi Markets; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Vertical lines indicate the start of US-China trade war, the start of the

COVID-19 pandemic, and the start of the Ukraine war, respectively.

26.4

7.1

5.3

11.4

–3.7

–24.7

18.6

–22.1

–6.9 –17.8 –31.3 –44.3 –31.9

–3.2 –8.7

–11.7 –2.4

–23.7 –49.2

–4.4

27.6 2.9 9.9 18.1 –22.3 13.9 –11.5

7.5

–11.7

9.3 –0.9 –9.8 –19.7 8.6

18.6 27.3 14.9 34.0 5.9 –13.3 27.6

9.2 0.6 19.4 2.3 –40.6 21.6

Figure 4.5. Foreign Direct Investment Reallocation across

Regions, 2020:Q2–22:Q4 versus 2015:Q1–20:Q1

(Percentage point deviation from aggregate change)

The regional shift in foreign direct investment flows shows winners and losers.

Source regions

Rest of

the world

China

Asia excl.

China

Emerging

Europe

Advanced

Europe

Americas

excl. US

United States

United

States

Americas

excl. US

Advanced

Europe

Emerging

Europe

Asia

excl.

China

China

Rest of

the

world

Destination regions

Sources: fDi Markets; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure shows deviation of regional foreign direct investment change from

aggregate change (19.5 percent decline). Changes are computed using the number

of greenfield foreign direct investments in 2020:Q2–22:Q4 and average number in

2015:Q1–20:Q1. Green (red) shading denotes positive (negative) numbers.

Excl. = excluding.

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

96 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

In regard to outward FDI from the US, the bot-

tom row of Figure 4.5 shows that US FDI to China

declined by much more than the average global decline.

At the same time, US FDI to other regions—and

particularly to emerging Europe—was more resilient.

is shift in the composition of outward US FDI can

be analyzed in detail, looking at differences between

host economies (Figure 4.6). Among major Asian and

European recipients of US FDI, some of the relative

winners (for example, Canada, Korea) are politically

closer to the US than the relative losers (for example,

China, Vietnam). is suggests that geopolitical factors

have driven part of the shift in FDI flows in recent

years. e next section investigates this issue in detail.

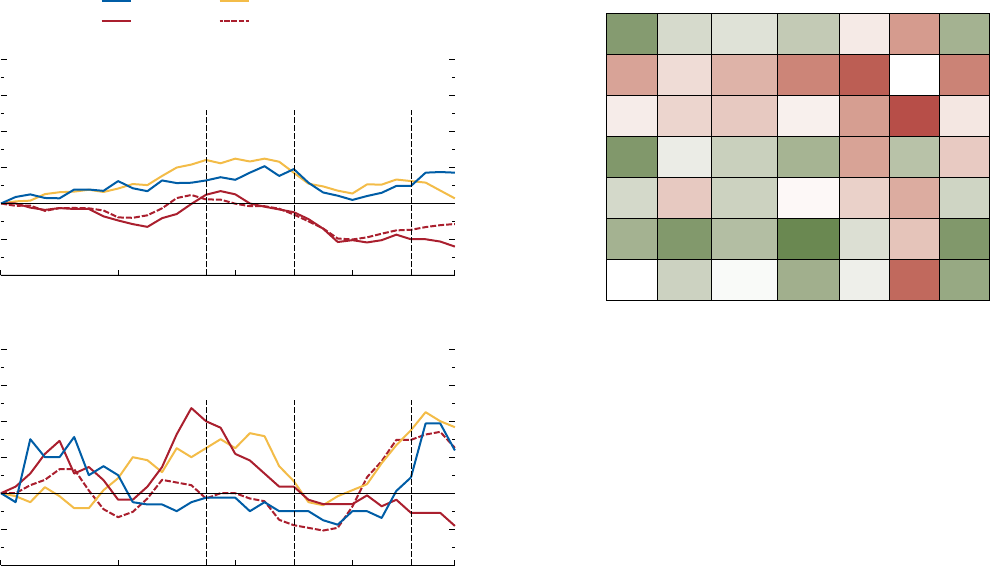

FDI Is Becoming More Responsive to Geopolitical Factors

Rising geopolitical tensions are a key driver of

FDI fragmentation, as bilateral FDI is increasingly

concentrated among countries that share similar

geopolitical views (Figure 4.7). is chapter measures

geopolitical alignment between countries using the

“ideal point distance” proposed by Bailey, Strezhnev,

and Voeten (2017), which is based on the similarity

of voting patterns at the United Nations General

Assembly.

7

As transportation costs and geographic

frictions also influence FDI decisions (Alfaro and

Chen 2018; Ramondo, Rodríguez-Clare, and Tintelnot

2015), it is informative to compare their roles with

that of geopolitical alignment. e share of FDI

among countries that are geopolitically aligned is larger

than the share going to countries geographically close,

suggesting that geopolitical preferences play a key role

as a driver of FDI. In addition, the importance of geo-

political alignment has increased over the last decade,

7

Recent analysis of geoeconomic fragmentation looks at recent

votes, such as the UN General Assembly vote on Resolution ES-11/1

on aggression against Ukraine on March 2, 2022 (Chapter 3 of

the October 2022 Regional Economic Outlook: Asia and Pacific;

Javorcik and others 2022). However, this chapter looks at the role of

geopolitical alignment over a longer period: the last 20 years. In this

respect, the ideal point distance has the advantage of being compa-

rable over time. Although the ideal point distance is widely used in

political science and in economics, scholars have proposed alternative

measures. e findings of the chapter are robust to the use of the

S score used in the April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report and

proposed by Signorino and Ritter (1999), who assign numeric values

to voting behavior in the UN General Assembly and calculate the

degree of disagreement between two countries by computing the

sum of squared differences of these values.

–40

0

40

80

120

CRI

COL

IND

CAN

KOR

TWN

MYS

SGP

AUS

MEX

BRA

VNM

JPN

ARG

PHL

HKG

CHN

Sources: fDi Markets; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure shows the deviation of outward US foreign direct investment change

by destination from aggregate change (24 percent decline). Changes are

computed using the number of greenfield foreign direct investments from the

United States to Europe and Asia in 2020:Q4–22:Q2 and average number in

2015:Q1–20:Q1. Labels on the x-axis use International Organization for

Standardization (ISO) country codes. “TWN” refers to “Taiwan Province of China.”

US foreign direct investment partly shifted from less to more aligned countries.

Figure 4.6. Change in Outward US Foreign Direct Investment,

2020:Q2–22:Q4 versus 2015:Q1–20:Q1

(Percentage point deviation from aggregate change)

Geopolitical distance Geographical distance

30

35

40

45

50

55

2003 06 09 12 15 18 21

Figure 4.7. Foreign Direct Investment between

Geographically and Geopolitically Close Countries

(Percent)

Sources: Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); Centre d’études prospectives et

d’informations internationales, Gravity database; fDi Markets; and IMF staff

calculations.

Note: Figure shows the annual share of total foreign direct investments between

country pairs that are similarly distant (that is, in same quintile of distance

distribution), geopolitically and geographically, from the United States.

The importance of geopolitical distance for foreign direct investment has

increased.

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

97International Monetary Fund | April 2023

and increased more steeply than the importance of geo-

graphic distance, especially for FDI in strategic sectors.

e role of geopolitical alignment is significant and

economically relevant, particularly for emerging market

and developing economies, in a gravity model that con-

trols for other potential drivers of FDI flows. In the base-

line specification, an increase in the ideal point distance

from the first to the third quartile of its distribution

(equivalent to moving the distance from that between

Canada and Japan to that between Canada and Jordan)

is associated with a decline in FDI between countries of

about 17 percent. is average effect is much stronger

when emerging market and developing economies are

either a source or a host country. Moreover, since 2018,

coincident with increasing trade tensions between China

and the US, geopolitical factors have become more rele-

vant to FDI flows. Finally, the analysis suggests that these

factors matter more in regard to investments in strategic

sectors (Figure 4.8). us, if countries move farther apart

along geopolitical fault lines, FDI is likely to become

more concentrated within blocs of geopolitically aligned

countries. Moreover, fragmentation risks are not confined

to FDI flows. Zooming in on non-FDI flows points out

a sharp increase in countries’ exposure to financial frag-

mentation risk, which could trigger a significant global

reallocation of capital in response to a rise in geopolitical

tensions (Box 4.2). Such tensions matter significantly

for cross-border portfolio allocation and could cause a

sudden reversal of cross-border capital flows, especially

in emerging market and developing economies (see the

April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report).

e findings reported in Figure 4.8 are based on a

gravity model that takes bilateral FDI as the depen-

dent variable and controls for standard push-and-pull

factors, including a set of time-varying fixed effects for

source and host countries (Kox and Rojas-Romagosa

2020).

8

To minimize the possibility that the coefficient

8

e analysis is based on estimating the following specification:

= f

(

α IPD

sdt−1

+ β Gravity

sd

+ τ

st

+ υ

dt

, ε

sdt

)

, where bilateral FDI flows

(measured by the number of investments) from the source country s

to the host country d in year t is a function of the lagged value of IPD

(the ideal point distance) between countries d and s. As is standard in

gravity models, the specification controls for the geographic distance

between source and host countries and other standard gravity controls,

and absorbs any time-varying unobservable push-and-pull factors,

adding source country × year and host country × year fixed effects.

ese fixed effects would capture, for instance, business cycle dynam-

ics that could push FDI outflows from a source country and attract

inflows into a host country. As, by construction, most of the FDI

sdt

cells are 0, the model is estimated using Poisson pseudo-maximum

likelihood (Santos Silva and Tenreyro 2006). Standard errors are

clustered at the country-pair level.

on the index of geopolitical distance captures the

role of other factors that could drive FDI, the model

is augmented to include measures of geographic,

cultural, and institutional distance and a historical

measure of colonial ties. As expected, the inclusion

of these variables—which are indeed associated with

bilateral FDI flows—reduces the size of the coefficient

of the ideal point distance, which however remains

statistically and economically significant. e findings

are also robust to considering FDI in manufacturing

or services separately; excluding financial centers or

China; controlling for the announcement and imple-

mentation of bilateral trade barriers, for the volume of

bilateral trade, and for exchange rate effects; measuring

FDI by its size rather than the number of investments;

and considering cross-border mergers and acquisitions

rather than greenfield FDI. e methodology and the

results are described in Online Annex 4.1.

Which Host Countries Are More Vulnerable to

FDI Relocation?

To assess the exposure of the stock of FDI hosted

by an economy to geoeconomic fragmentation, the

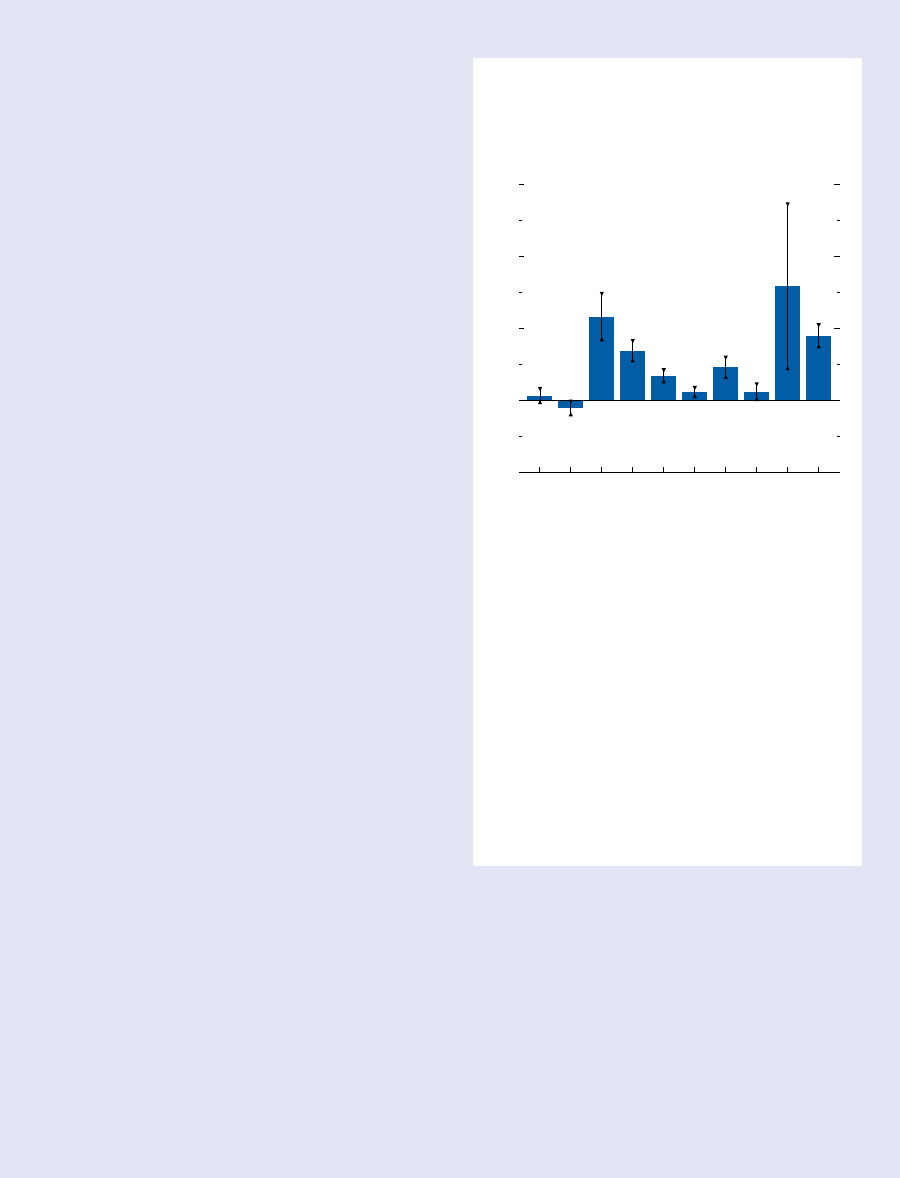

Time periodsStrategic

sectors

Income groups

Strategic

Nonstrategic

2018–21

2009–17

2003–08

EMDEs (destination)

EMDEs (source)

AEs (destination)

AEs (source)

All

–0.4 –0.3 –0.2 –0.1 0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3

Sources: Atlantic Council; Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); Centre d’études

prospectives et d’informations internationales, Gravity database; fDi Markets; NL

Analytics; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Coefficients of ideal point distance are estimated from gravity model for

number of foreign direct investments. See Online Annex 4.1 for details.

AEs = advanced economies; EMDEs = emerging market and developing

economies.

Greater geopolitical distance is associated with less foreign direct investment,

especially in EMDEs, in recent years and in strategic sectors.

Figure 4.8. Gravity Model for Ideal Point Distance and

Foreign Direct Investment

(Semielasticities)

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

98 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

chapter develops a multidimensional index of vulner-

ability. It combines three subindices, based on three

dimensions relevant to geoeconomic fragmentation:

(1) the geopolitical distance between source and

host countries, (2) the degree of market power that

host countries have in each industry in which they

receive FDI, and (3) the strategic component of the

stock of FDI.

• The geopolitical index captures the idea that the

greater the geopolitical distance between source

and host countries, the greater the vulnerability

to friend-shoring. The index is calculated for each

host country by multiplying the share of invest-

ment from each source country by the geopolit-

ical distance between host and source countries.

Given that most countries receive much of their

FDI from advanced economies and given that

those economies are geopolitically closer to one

another than to emerging market and develop-

ing economies, these economies are more geo-

politically vulnerable than advanced economies

(Figure 4.9, panel 1).

• Countries with high market shares in trade of a

given sector may be less vulnerable to relocation

pressures in that sector, as foreign investors may

have fewer options for relocating investment. The

index of market power captures this dimension by

treating FDI in a particular sector as less vulnerable

if the host country is among the top 10 exporters in

that sector. By contrast, FDI in host countries that

are not among the top 10 exporters in that sector is

treated as fully vulnerable. Though the vast majority

of economies show low levels of protection from

market power, some large economies (for exam-

ple, China, Germany, US) do enjoy some level of

protection, being large exporters in many sectors

(Figure 4.9, panel 2).

• The strategic index measures the share of inward

FDI in strategic sectors. This dimension of vulner-

ability shows substantial overlap between advanced

and emerging market and developing economies

(Figure 4.9, panel 3).

e geopolitical and strategic dimensions of

vulnerability are broadly uncorrelated and capture

distinct aspects of countries’ vulnerability to geoeco-

nomic fragmentation (Figure 4.10). Whereas geopo-

litical vulnerability is concentrated among emerging

market and developing economies—as shown by the

disproportionate share of red squares in the figure

Germany China

China

Germany

United

States

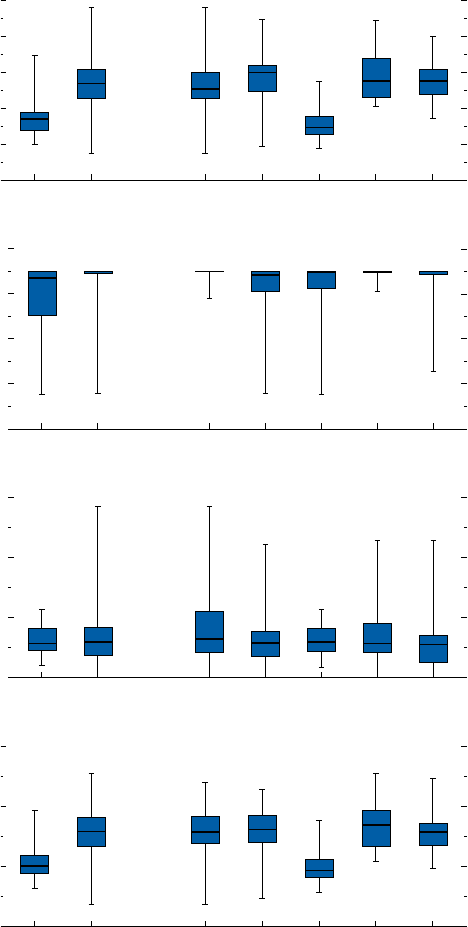

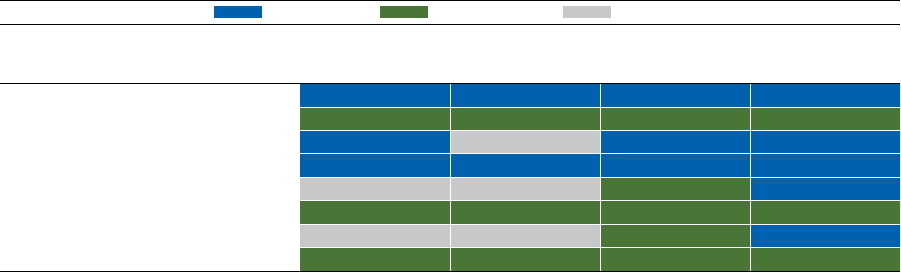

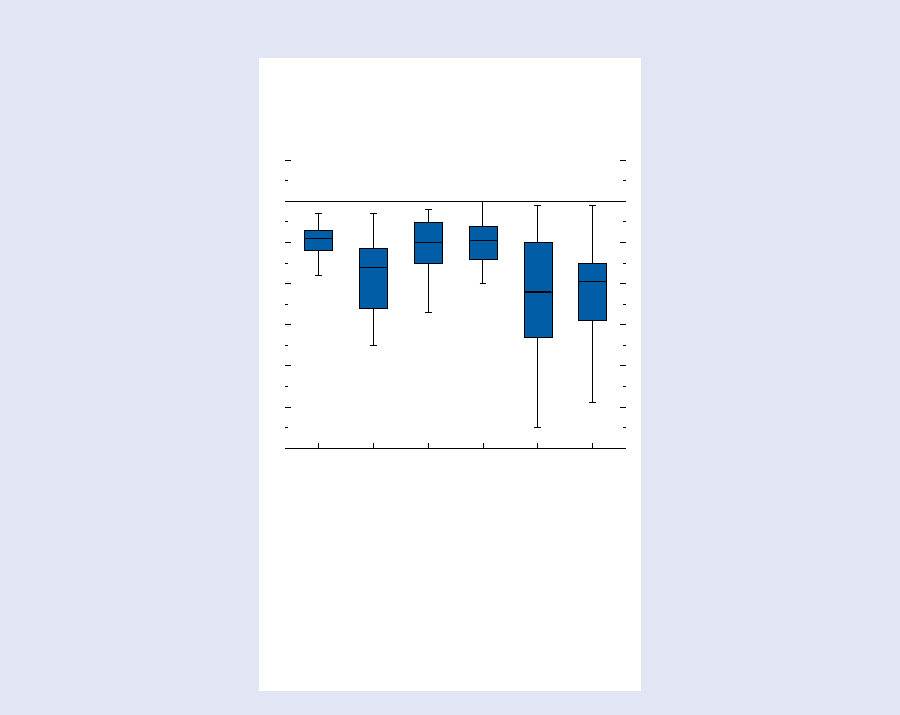

Figure 4.9. Vulnerability Index

Emerging market and developing economies tend to be more vulnerable to

relocation of foreign direct investment than advanced economies.

1. Geopolitical

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

AEs EMDEs SSA Europe Americas

Asia-Pacific MENAP-CCA

2. Market Power

0.65

0.75

0.85

0.95

1.05

AEs EMDEs SSA Europe Americas

Asia-Pacific MENAP-CCA

3. Strategic

0.00

0.15

0.30

0.45

AEs EMDEs SSA Europe Americas

Asia-Pacific MENAP-CCA

4. Aggregate

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

AEs EMDEs SSA Europe Americas

Asia-Pacific MENAP-CCA

Sources: Atlantic Council; Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); fDi Markets; NL

Analytics; Trade Data Monitor; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure shows distribution of vulnerability index by income and regional

groups, based on post-2009 foreign direct investment flows. AEs = advanced

economies; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies;

MENAP-CCA = Middle East, North Africa, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Caucasus, and

Central Asia; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa.

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

99International Monetary Fund | April 2023

to the right of the vertical line denoting the median

geopolitical index—many large advanced economies,

including the US, Germany, and Korea, are in the

top half of the distribution of strategic vulnerability.

e cluster of countries particularly vulnerable along

both dimensions includes some large emerging market

economies, such as Brazil, China, and India, but also

several other emerging market economies, suggesting

that FDI fragmentation is likely to be an issue for a

large set of countries.

e three subindices are combined to construct

an aggregate index. e aggregate index adds the

strategic and geopolitical dimensions, with the latter

multiplied by the market power index. Multiplying

the geopolitical dimension by the market power

index—bounded between 0 and 1—allows for a

dampening of the geopolitical vulnerability com-

ponent. is captures the idea that multinationals

that would like to move their investments out of

geopolitically distant countries will find it more

difficult to do so if the host country is a key player

in the global market in that sector. e strategic

dimension is added to the combined geopolitical and

market power component, as it reflects the height-

ened vulnerability of investments in specific sectors

in all host countries, not only those that are geopo-

litically distant, and such sectors are more likely to

be targeted with reshoring policies, offsetting any

protection from market power.

9

Overall, emerging

market and developing economies are more vulnera-

ble to FDI fragmentation than advanced economies,

even if there is large variation in the distribution of

the index and some overlap between advanced and

emerging market economies (for instance, 14 percent

of emerging market and developing economies have

a vulnerability index lower than the median for

advanced economies). e distribution across regions

shows the better position of Europe, while all other

regions show higher and similar levels of vulnerability

(Figure 4.9, panel 4).

While the aggregate vulnerability index is

intended to describe exposures of existing stocks to

relocation as they stand, policy measures could help

reduce future vulnerabilities. Beyond multilateral

9

Rather than simply combining a host country’s scores for the

three subindices, the aggregate index is built up from the sector–

source country level, such that market power offsets geopolitical

distance only for sectors in which the host economy is among the

top 10 exporters. e methodology for constructing the vulnerability

indices is discussed in Online Annex 4.2.

efforts to preserve cooperation, domestic policies

could also help, allowing economies to mitigate

some risks even in a geopolitically tense world.

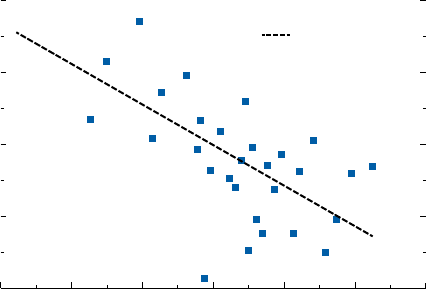

Figure 4.11 suggests that stronger regulatory quality

tends to be associated with lower aggregate vulner-

ability to relocation of FDI. Improved regulatory

quality tends also to be associated with higher

exports, which could offer protection against reloca-

tion pressures.

FDI Spillovers to Host Countries

Besides direct effects on job creation and capital

formation, inward FDI could have spillover effects

on domestic firms through technology diffusion,

backward and forward linkages, and productivity

gains from increased competition.

10

When it comes

to empirical results, however, the effects are mixed

(Görg and Greenaway 2004; Bénétrix, Pallan, and

Panizza 2022). Cross-country studies reveal that the

effect of inward FDI is uneven and depends on host

10

Formal descriptions of each channel are developed in

Rodríguez-Clare (1996) for backward and forward linkages, Glass

and Saggi (1998) for the technology spillover effect, and Barba

Navaretti and Venables (2004) for the pro-competitive effect. For

a more skeptical view on the gains from financial integration, see

Gourinchas and Jeanne (2006).

Advanced economies

Emerging market and

developing economies

SYC

GUY

CPV

BLZ

ZAF

HUN

VNM

IND

CHN

BRA

KOR

ITA

FIN

USA

DEU

Figure 4.10. Geopolitical Index and Strategic Index

Strategic and geopolitical indices capture distinct vulnerabilities.

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

Strategic index

0.00 0.25 0.50 0.75 1.00

Geopolitical index

Sources: Atlantic Council; Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); fDi Markets; NL

Analytics; Trade Data Monitor; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Data are based on post-2009 foreign direct investment flows. Horizontal line

indicates the median value of strategic index, 0.09, and vertical line indicates the

median value of geopolitical index, 0.5. Labels in the figure use International

Organization for Standardization (ISO) country codes.

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

100 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

countries’ human capital (Borensztein, De Gregorio,

and Lee 1998), institutional quality (Kose and others

2009), and financial development (Alfaro and others

2004). e lack of consistent findings may stem from

FDI heterogeneity along the mode of entry, the type

of investment, and the relationship between foreign

and domestic firms. e evidence is generally more

informative for specific types of FDI and spillovers

along the value chain (Harrison and Rodríguez-Clare

2010). Hence, the analysis here explores two important

dimensions: the distinction between horizontal and

vertical FDI and differences in spillovers within and

across industries.

11

Horizontal versus Vertical FDI

Horizontal FDI refers to foreign firms entering a

country to directly serve local markets. By contrast,

vertical FDI takes place when foreign firms enter

a country to produce inputs that will be supplied

11

e interpretation of the results should take into account the

potential endogeneity of FDI, which is in part addressed by using

lagged values of FDI and including fixed effects (especially in the

firm-level analysis).

to affiliated firms.

12

is distinction is particularly

relevant in the context of geoeconomic fragmentation,

given that vertical FDI is likely more exposed to FDI

fragmentation risk than horizontal FDI. Higher trade

barriers, for instance, would make horizontal FDI

more attractive—as it could be a substitute for trade

(Brainard 1997)—while making vertical FDI less

attractive. Moreover, vertical FDI is often centered on

advanced technology embodied in input production

and thus is more likely to be the target of policies

aimed at reshoring strategic production.

Vertical FDI is positively associated with economic

growth, as it is concentrated among intermediate-goods

producers that adopt more sophisticated (and

skill-intensive) technology (Atalay, Hortaçsu, and

Syverson 2014; Ramondo, Rappoport, and Ruhl

2016). is is not the case for horizontal FDI, more

likely to be found among final-goods producers, which

tend to transfer simple (and labor-intensive) assembly

technology to host countries (Figure 4.12). ese find-

ings are obtained from cross-country growth regres-

sions, which are estimated separately for countries

more likely to receive vertical or horizontal FDI.

13

Spillovers within and across Industries

e effects of the entry of a multinational corpo-

ration on domestic firms could be different depend-

ing on whether those firms are in the same sector

or in other sectors—either upstream or downstream

along the value chain. For instance, consider Toshiba

setting up a chip-making plant in China. e Chinese

chipmakers are directly affected by the entry of

Toshiba (within-industry spillovers), as the increased

competition can either provide local firms with a

greater incentive to innovate, and thus to become

more productive, or crowd out local firms by stealing

12

e Samsung Electronics smartphone factory in India is

an example of horizontal FDI, as most of its products are sold

to Indian customers, whereas its semiconductor factory in

Vietnam is an example of vertical FDI, as its products are sold

mainly to Samsung’s own affiliates worldwide. Other relatively

minor types of FDI include export-platform FDI (for example,

Volkswagen’s plant in Mexico, which sells mostly to the US) and

export-supporting FDI (for example, Toyota Financial Services

USA, which offers US consumers financing options to facilitate

export sales from Japan).

13

is classification is based on detailed foreign subsidiary–level

sales information from the Export-Import Bank of Korea. e esti-

mation results are robust to alternative classifications based on parent

and subsidiary firms’ sector affiliations from Orbis. e methodology

and the results are described in more detail in Online Annex 4.3.

Linear fit

Figure 4.11. Vulnerability Index and Regulatory Quality

Higher regulatory quality is associated with lower vulnerabilities.

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

0.40

Aggregate vulnerability index

–1.5 –0.5–1.0 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5

Regulatory quality index

Sources: Atlantic Council; Bailey, Strezhnev, and Voeten (2017); fDi Markets; NL

Analytics; Trade Data Monitor; World Bank, World Governance Indicators; and IMF

staff calculations.

Note: Sample includes a cross section of 128 countries. The binned scatterplots

are obtained from a regression of the aggregate vulnerability index against the

regulatory quality index, controlling for the logarithm of real GDP, trade (percent of

GDP), and foreign direct investment inflows (percent of GDP). All variables are

averaged over 2010–19. The regressions give a coefficient of the regulatory

quality index equal to –0.057 (p-value of 0.000).

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

101International Monetary Fund | April 2023

market share (Markusen and Venables 1999). At the

same time, there are spillovers to other industries

(cross-industry spillovers): Chinese silicon produc-

ers are also affected as they are big suppliers to the

chip-making industry (backward linkages). Moreover,

Chinese firms in the automobile industry will also be

affected as they are heavy users of semiconductor chips

(forward linkages).

Results based on a large sample of firm-level data

from the World Bank Enterprise Surveys covering

over 120,000 firms in 150 countries from 2006 to

2021 show positive spillovers to domestic firms in

the same industry (Figure 4.13, top graph). Positive

within-industry spillovers to firms’ labor productivity

are confined to advanced economies, where firms react

to fiercer competition from multinational corpora-

tions by becoming more productive. In the case of

cross-industry spillovers, domestic suppliers benefit

from the entry of foreign firms in downstream sectors,

as the latter may source inputs locally and increase

local demand for inputs produced by domestic firms.

Local suppliers may also benefit from learning by

doing via direct contact with foreign buyers with

better technology. ese positive spillovers to domestic

suppliers are driven by FDI in emerging market and

developing economies.

14

By contrast, there is no evi-

dence of spillovers to domestic users, even in emerg-

ing market and developing economies. is could be

because foreign firms in upstream sectors mostly sell

abroad, implying limited scope for positive technol-

ogy spillovers via direct contact with local buyers

(Figure 4.13, bottom two graphs).

A Model-Based Quantification of the Costs of

FDI Fragmentation

To investigate the long-term implications of poten-

tial FDI fragmentation, this section uses a multiregion

DSGE model to explore possible scenarios.

15

e sim-

ulations focus on fragmentation of investment flows

14

ese findings are consistent with those of Mercer-Blackman,

Xiang, and Khan (2021) on a smaller sample covering mostly

Asian countries.

15

e analysis uses the IMF’s Global Integrated Monetary and

Fiscal Model, further elaborated in Online Annex 4.4. A detailed

exposition of the model and its properties may be found in Kumhof

and others (2010) and Anderson and others (2013).

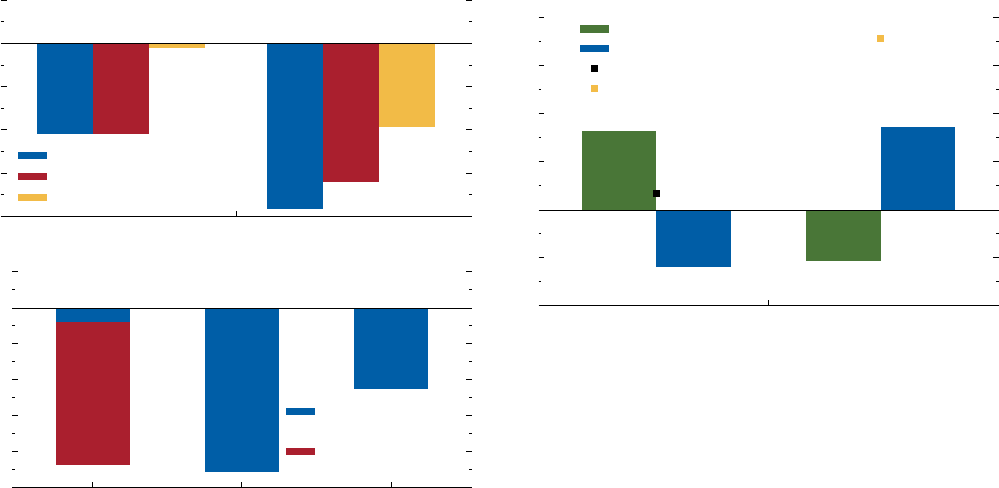

Figure 4.12. Foreign Direct Investment and Growth:

Horizontal versus Vertical

(Standardized coefficients)

Vertical foreign direct investment is associated with higher GDP growth in

emerging market and developing economies.

All

AEs

EMDEs

Vertical

All

AEs

EMDEs

Horizontal

–0.05 0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15

Sources: Export-Import Bank of Korea; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure reports the standardized coefficients obtained from cross-country

growth regression estimated separately for countries with horizontal foreign direct

investment and those with vertical. Solid bars indicate statistical significance at

1 percent level. See Online Annex 4.3 for details. AEs = advanced economies;

EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

Figure 4.13. Firm-Level Foreign Direct Investment Spillovers:

within Industries versus across Industries

(Standardized coefficients)

Foreign direct investment spillovers take place within industries in advanced

economies, while domestic suppliers benefit from foreign direct investment in

emerging market and developing economies.

–0.4–0.6 –0.2 0.0 0.2 0.4

Sources: Eora Global Supply Chain Database; fDi Markets; World Bank Enterprise

Survey; and IMF staff calculations.

Note: Figure reports the standardized coefficients obtained from firm-level

regression of labor productivity growth as a function of foreign direct investment

within and across industries. Solid bars indicate statistical significance at

1 percent level. See Online Annex 4.3 for details. AEs = advanced economies;

EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies.

Within industries

All

AEs

EMDEs

All

AEs

EMDEs

All

AEs

EMDEs

Domestic

supplier

Domestic

user

Across industries

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

102 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

arising from permanent barriers between geopolitical

blocs, as well as heightened uncertainty about the geo-

political alignment of different regions. e analysis,

and the various hypothetical scenarios, are intended to

illustrate some of the key economic mechanisms likely

to be at play and to provide a sense of overall output

losses and the distribution of costs and benefits across

economies, including those from spillovers through

external demand and the reallocation of production

capacity. e geopolitical coalitions considered are for

analytical purposes only and are not intended to indi-

cate alignment choices countries are likely to make.

e analysis focuses on two key roles of FDI:

its contribution to capital formation in host econ-

omies and the transmission of technologies and

productivity-enhancing management practices from

advanced to emerging market and developing econ-

omies. e model does not have explicit foreign

ownership of productive capital, and thus there is no

direct mapping to FDI.

16

e bilateral cross-border

flow of inputs into investment is instead used as a

proxy, since similarly to reductions in FDI, barriers to

the flow of such inputs directly reduce capital forma-

tion. e scenarios illustrate a 50 percent reduction

of such flows. Alongside, empirical estimates of the

correlation between FDI flows and labor productivity

are used to discipline the associated productivity losses

from a reduction in such flows. e analysis comple-

ments the literature, which has focused on the impact

of fragmentation through trade and associated knowl-

edge spillovers (Cerdeiro and others 2021; Eppinger

and others 2021; Góes and Bekkers 2022; Javorcik and

others 2022), although a full analysis of the interaction

between different aspects of geoeconomic fragmen-

tation is beyond the scope of this chapter. Box 4.3

discusses new evidence suggesting that the fragmen-

tation of international trade as a result of geopolitical

tensions could lead to lower output in most countries,

with emerging market and developing economies more

adversely affected than other country groups.

e simulations center on decoupling between the

two largest economies—China and the US—which is

likely to be the most economically consequential form

of fragmentation. Although how other countries and

regions might align themselves in such a decoupling

remains unclear and will depend on a multitude of

16

With a few exceptions (Arkolakis and others 2018;

Reyes-Heroles, Traiberman, and Van Leemput 2020), multicountry

trade models used in the literature tend to abstract from investment.

factors (for example, strength of existing trade and

financial links and national security considerations),

scenario analysis is used to highlight the implications

of different geopolitical-alignment choices for eco-

nomic outcomes.

e model allows for up to eight regions. China,

the EU+ (that is, the EU and Switzerland), and the

US are assigned their own regions, as the policy

choices of these economies are likely to shape global

fragmentation scenarios. To illustrate the interaction

between alignment choices and economic outcomes for

emerging market and developing economies, includ-

ing through investment diversion, a region is assigned

to Latin America and the Caribbean and another to

India and Indonesia, two representative Asian emerg-

ing market and developing economies with relatively

neutral measures of geopolitical distance from the US

and China. e remaining three regions comprise the

rest of southeast Asia, other advanced economies (for

example, Australia, Canada, Japan, UK), and the rest

of the world (for example, central Asia, Middle East,

Russia, sub-Saharan Africa).

While geopolitical-alignment choices are highly

uncertain, to discipline the analysis, the chapter con-

structs a baseline hypothetical scenario for alignments

using the ideal point distance. Relative distances from

either the US or China, based on the latest ideal point

distance data, are used to assign regions to geopolit-

ical blocs aligned with either the US or China, or as

nonaligned. Additional scenarios, focusing on different

alignment choices for the EU+, India and Indone-

sia, and Latin America and the Caribbean, explore

the interaction between geopolitical alignment and

economic outcomes (Table 4.1). In reality, geopolit-

ical alignments are not givens and likely require the

balancing of multiple considerations (beyond the scope

of this chapter) under frictions and uncertainty.

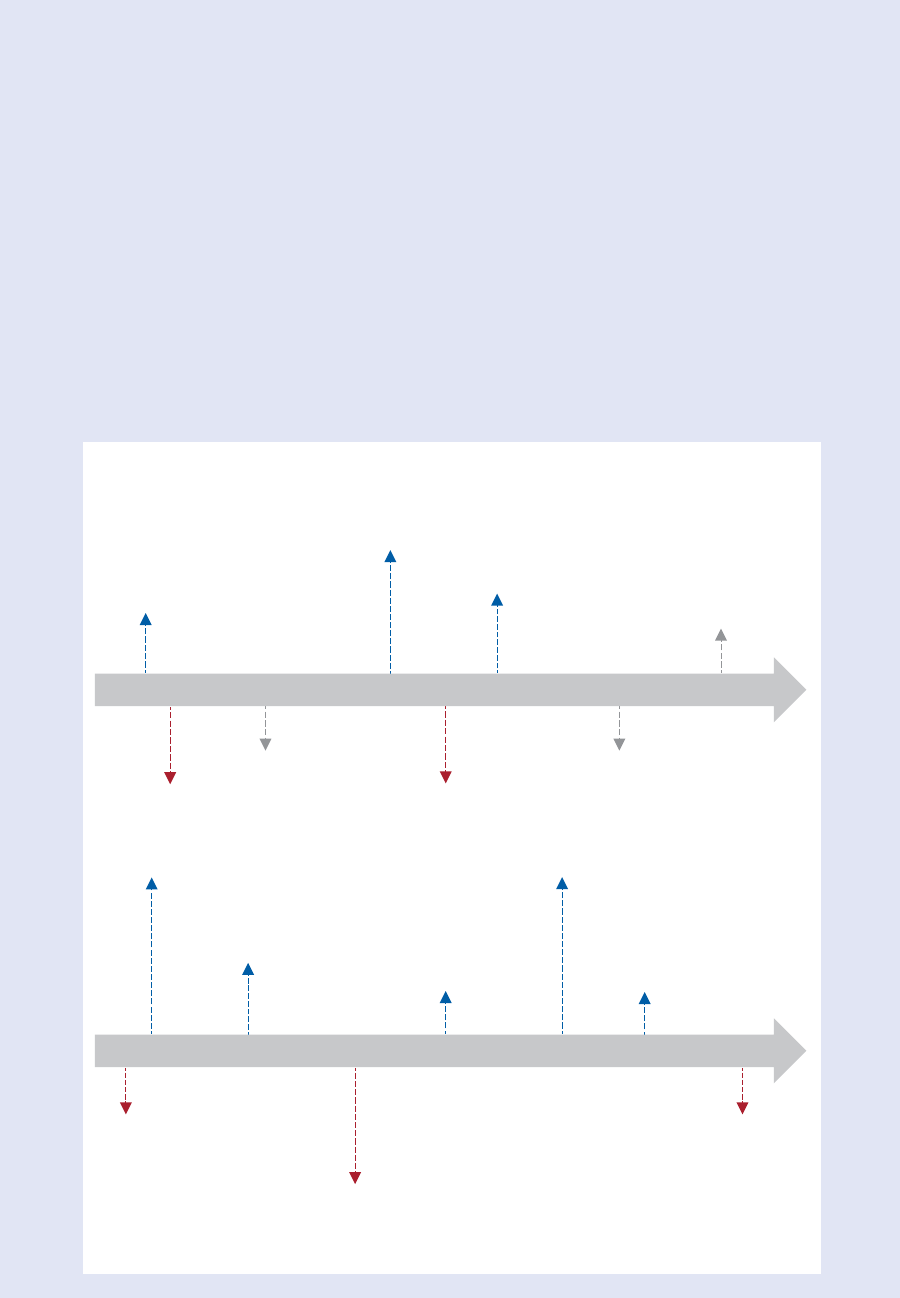

In the first scenario, in which the world splin-

ters into a US-centered bloc and a China-centered

bloc, and with both India and Indonesia and Latin

America and the Caribbean remaining nonaligned,

global output is about 1 percent lower after five years

(relative to the no-fragmentation scenario). Global

output losses increase as the impact on capital stocks

and productivity from lower investment input flows

cumulate, with long-term output lower by 2 percent

(Figure 4.14). Output losses are generally larger in

the emerging-market-dominated China bloc, as these

regions face heightened barriers to the major sources of

investments, namely, advanced economies. e losses

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

103International Monetary Fund | April 2023

are also nonnegligible for the US bloc, however, driven

by some members’ strong links to China (such as Japan

and Korea in the other advanced economies region and

Germany in the EU+ region).

For the nonaligned economies, the impact depends

on the outcome of two competing channels. On the

one hand, the substantial reduction in global activity

reduces external demand, weighing on net exports

and investment. On the other hand, these regions also

benefit from the diversion of investment flows, which—

if sufficiently large—could boost investment and

output. e importance of the second channel increases

with the ease with which investment goods from

different regions can be substituted for one another by

the importing region. In the benchmark assumption

for the elasticity of substitution across source regions of

investment inputs, the first channel dominates, and the

nonaligned regions experience a small drop in output

(Figure 4.14, darker bars). Alongside the benchmark

case, an alternative case uses a higher elasticity of substi-

tution (double in value). In the alternative case, higher

diversion yields a small net increase in investment and

output (Figure 4.14, lighter bars).

17

In reality, a geoeconomically fragmented world might

entail substantial policy uncertainty for economies that

try to remain open to both geopolitical blocs. Rather

than having their nonaligned status accepted, these

economies may need to walk a narrow path amid pres-

sures from both sides, with the attendant risk of falling

out with one bloc or the other. is type of policy

17

Similar to the cases of India and Indonesia and Latin America

and the Caribbean, losses are significantly lower for other regions,

such as southeast Asia, if they are also nonaligned, as shown in

additional simulations in Online Annex 4.4.

uncertainty, in which investors perceive a risk that

current policy stances toward that economy could shift

radically in the future, can act as an economically mean-

ingful barrier to trade and investment, as documented

in the literature (for example, Handley and Limão

2022). While the exact degree of such uncertainty in

a hypothetical fragmented future is impossible to pin

down, a case involving a high level of uncertainty—in

which investors in both blocs perceive a 50 percent

chance that the nonaligned region will fall in with the

opposing bloc over the long term—is a natural analyti-

cal complement to the baseline no-uncertainty scenario

already discussed.

18

Specifically, investors behave as if

investment input flows to (from) these regions face half

the barriers faced by regions in the opposing bloc. As

shown in Figure 4.15, losses are significantly amplified

for nonaligned regions under such uncertainty, as they

face reduced inflows from both blocs, with some nega-

tive spillovers to other regions as well.

Alternative alignment choices highlight their sig-

nificant impact on outcomes. For example, a world

in which the EU+ remains nonaligned entails sig-

nificantly lower costs for both itself and the China

bloc economies. However, the EU+ might face

heavy costs if such a policy approach significantly

raises the possibility of barriers between itself and

the US—due to greater uncertainty about its future

alignment (Figure 4.16, panel 1). Under the base-

line, the two nonaligned regions generally tend to be

18

e scenario illustrates the case with India and Indonesia and

the Latin America and Caribbean regions remaining nonaligned

indefinitely, but with investors perceiving a risk they will pick a side

in the future (and therefore face the associated barriers). Alongside

the 50–50 scenario presented here, Online Annex 4.4 discusses a

range of possible levels of uncertainty.

Table 4.1. Modeled Fragmentation Scenarios

US Bloc China Bloc Nonaligned

Model Region

GDP Share (Percent)

Two Blocs +

Nonaligned EMDE

Regions Nonaligned EU+

Nonaligned EMDEs

Join China Bloc

Nonaligned EMDEs

Join US Bloc

United States

16.0

China

17.5

EU+

15.6

Other AEs

13.8

India and Indonesia

9.6

Southeast Asia

4.0

LAC

6.5

ROW

17.0

Source: IMF staff compilation.

Note: AEs = advanced economies; EMDEs = emerging market and developing economies; EU+ = European Union and Switzerland; LAC = Latin America and the

Caribbean; ROW = rest of the world.

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

104 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

worse off when aligning with either bloc, as opposed

to remaining open to both. However, given that the

advanced-economy-dominated US bloc is the major

source of investment flows, they are better off joining

this bloc if forced to choose, especially if they were to

face uncertainty otherwise (Figure 4.16, panel 2).

Blocs’ incentive to attract emerging market and

developing economies might give nonaligned regions

some bargaining power but could also generate the

type of damaging uncertainty that reduces investment

(Figure 4.17). Unsurprisingly, existing bloc members

would gain when their bloc attracts the nonaligned

regions and lose when nonaligned regions join the oppos-

ing bloc. e gain to the existing bloc members could

outweigh the losses to the joining regions, suggesting

some scope for transfers to implement such an outcome.

Potential transfers could take several forms, including

favorable trade and investment treatment or fiscal mea-

sures to encourage friend-shoring to target economies.

19

19

For example, see the announcement that the US will support invest-

ment in India by the largest US solar manufacturer (Sharma 2022).

e opposing bloc would likely want to avoid such an

outcome. In reality, alignment choices are likely to be

dependent on multiple considerations and subject to

coordination frictions, further underscoring the uncer-

tainty that could itself weigh on investment.

Policy Implications

e findings of this chapter contribute to under-

standing how fragmentation pressures may already be

affecting investment flows across economies, as well

as the long-term implications for the global economy

if such pressures lead to a substantial relocation of

FDI. Vulnerabilities to FDI fragmentation are broadly

shared across many emerging market and developing

economies, and advanced economies are not immune,

particularly those with significant FDI stocks in

strategic sectors. As vulnerabilities can also extend to

non-FDI flows (see the April 2023 Global Financial

Stability Report), a rise in political tensions could trig-

ger large reallocation of capital flows at the global level,

with effects particularly pronounced for emerging mar-

ket and developing economies. e chapter’s analysis

Cross-bloc investment barriers

Nonaligned uncertainty

Total

Figure 4.15. Long-Term GDP Losses, with Uncertainty for

Nonaligned Economies

(Percent deviation from no-fragmentation scenario)

Policy uncertainty could amplify losses for nonaligned economies.

0

1

–8

–7

–5

–6

–4

–3

–2

–1

United

States

EU+ Other

AEs

China SE

Asia

ROW India and

Indonesia

LAC World

US bloc China bloc Nonaligned

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: Darker bars denote scenario with lower elasticity of substitution (1.5)

between foreign sources of investment inputs. Lighter bars denote scenario with

higher elasticity of substitution (3.0) between foreign sources of investment inputs

and thus a greater role for diversion. AEs = advanced economies; EU+ = European

Union and Switzerland; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; ROW = rest of the

world; SE = Southeast.

Barriers to investment

Productivity losses

Medium-term total

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: Baseline fragmentation scenario represents barriers generating 50 percent

decline in investment input flows between China and US blocs, with no barriers

with two nonaligned regions (India and Indonesia and Latin America and the

Caribbean). Darker bars denote scenario with lower elasticity of substitution (1.5)

between foreign sources of investment inputs. Lighter bars denote scenario with

higher elasticity of substitution (3.0) between foreign sources of investment inputs

and thus a greater role for diversion.

AEs = advanced economies; EU+ = European Union and Switzerland; LAC = Latin

America and the Caribbean; ROW = rest of the world; SE = Southeast.

Fragmentation could lower global output by up to 2 percent.

0

1

–7

–6

–5

–4

–3

–2

–1

United

States

EU+ Other

AEs

China SE

Asia

ROW India and

Indonesia

LAC World

US bloc China bloc Nonaligned

Figure 4.14. Impact of Investment Flow Barriers on GDP

(Percent deviation from no-fragmentation scenario)

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

105International Monetary Fund | April 2023

suggests that a fragmented global economy is likely

to be a poorer one. While there may be relative—and

possibly absolute—winners from diversion, such gains

are subject to substantial uncertainty.

e chapter does not attempt to measure the success

of the policies driving geoeconomic fragmentation in

meeting the objectives often ascribed to them, such as

enhancing national security or maintaining a tech-

nological advantage over rival countries, especially in

strategic sectors. Instead, its analysis highlights that

the pursuit of these objectives entails large economic

costs, not just for a country’s rivals and (possibly) other

nonaligned countries, but also for the country itself

and countries aligned with it. ese costs need to be

considered carefully.

In regard to policies, the large and widespread

economic costs from strategic decoupling provide a

rationale for a robust defense of global integration, at a

time when several actors are advocating more barriers

and inward-looking policies. For instance, increasing

diversification in international sourcing of inputs

away from domestic sources can make supply chains

more resilient to shocks (see Chapter 4 of the April

2022 World Economic Outlook), without imposing

costs on the world economy. At the same time, the

current rules-based multilateral system must adapt to

the changing world economy and should be com-

plemented by credible “guardrails” to mitigate global

spillovers and by domestic policies targeted at those

adversely affected by global integration (Aiyar and

others 2023).

As policy uncertainty amplifies losses from frag-

mentation, especially for nonaligned countries, effort

should be devoted to minimizing such uncertainty.

Improving information sharing through multilateral

dialogue would support this goal. In particular, the

development of a framework for international consul-

tations (for instance, on the use of subsidies to provide

incentives for reshoring or friend-shoring of FDI)

could help identify unintended consequences. It could

also mitigate cross-border spillovers by reducing uncer-

tainty and promoting transparency on policy options.

Finally, in a more geopolitically tense world, coun-

tries can reduce their vulnerability to FDI relocation

by implementing policies and regulations to pro-

mote private sector development. Moreover, a more

EU+ in US bloc

EU+ nonaligned, with uncertainty

EU+ nonaligned, no uncertainty

Uncertainty for

nonaligned

Cross-bloc investment

barriers

Figure 4.16. Impact on GDP for Bloc Members: Tripolar World

and Nonaligned Joining Blocs

(Percent deviation from no-fragmentation scenario)

1. Impact of Nonaligned EU+, with and without Uncertainty

–4

–3

–2

–1

0

1

EU+ China bloc

2. Impact of Nonaligned Joining Blocs

–2.5

–2.0

–1.5

–1.0

–0.5

0.0

0.5

Both nonaligned Both join China bloc Both join US bloc

Remaining nonalign

ed with certainty tends to limit losses.

Source: IMF s

taff calculations.

Note: EU+ = European Union and Switzerland.

China bloc

US bloc

China bloc, with new members

US bloc, with new members

–0.2

–0.1

0.0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

Nonaligned joining China bloc Nonaligned joining US bloc

Source: IMF staff calculations.

Note: The nonaligned include India and Indonesia and Latin America and the

Caribbean.

Figure 4.17. Impact on GDP for Bloc Members: Nonaligned

Joining Blocs

(Percent deviation from nonaligned scenario with uncertainty)

Blocs have incentives to attract nonaligned regions and discourage nonaligned

from joining the opposing bloc.

WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK: A ROCKY RECOVERY

106 International Monetary Fund | April 2023

fragmented world in which large economies implement

policies to promote friend-shoring of FDI could be

an opportunity for some countries to benefit from

diversion of investment flows by attracting new FDI.

Measures that can increase countries’ attractiveness as

investment destinations include undertaking structural

reforms (Campos and Kinoshita 2010), establishing

investment promotion agencies to reduce informa-

tion asymmetries and ease bureaucratic procedures

(Harding and Javorcik 2011; Crescenzi, Di Cataldo,

and Giua 2021), and improving infrastructure (Chen

and Lin 2020).

CHAPTER 4 GEOECONOMIC FRAGMENTATION AND FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

107International Monetary Fund | April 2023

is box provides a summary and timeline of recent

events behind US-China trade tensions, one of the

major drivers behind the rising risk of geoeconomic

fragmentation.

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization

(WTO) in 2001, following its ambitious economic

reforms of the 1990s, was a pivotal milestone, with

world trade volumes almost doubling since then

and China becoming the world’s top exporter and

second-largest economy. However, trade tensions

have been growing over the subsequent years as

China’s rapid export growth has affected segments

e author of this box is JaeBin Ahn.

of European and US industry. As China’s economic

reforms slowed and even reversed, major trading

partners became increasingly concerned by the

economic role of the state in domestic and export

markets, including technology transfer practices

and the footprint of state-owned enterprises with

an international presence. e inability of WTO

members to agree on reforms in these and other

sensitive areas has exacerbated trade tensions (Aiyar

and others 2023).

e US imposition of tariffs against China in July

2018 triggered an immediate Chinese response and

was followed by rounds of back-and-forth escala-

tions (Figure 4.1.1). e Phase One trade agreement

Box 4.1. Rising Trade Tensions

Jul.–Sep. 2018 Dec. 2018 May 2019 Aug. 2019 Jan. 2020 Feb.–Sep. 2020