CHILD AND FAMILY LAW

CLINIC

DEPENDENCY HANDBOOK

CHILD AND FAMILY LAW CLINIC

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA

JAMES E. ROGERS COLLEGE OF LAW

1145 North Mountain Ave

Tucson, AZ 85719

(520) 626 - 5232

Revised January, 2015

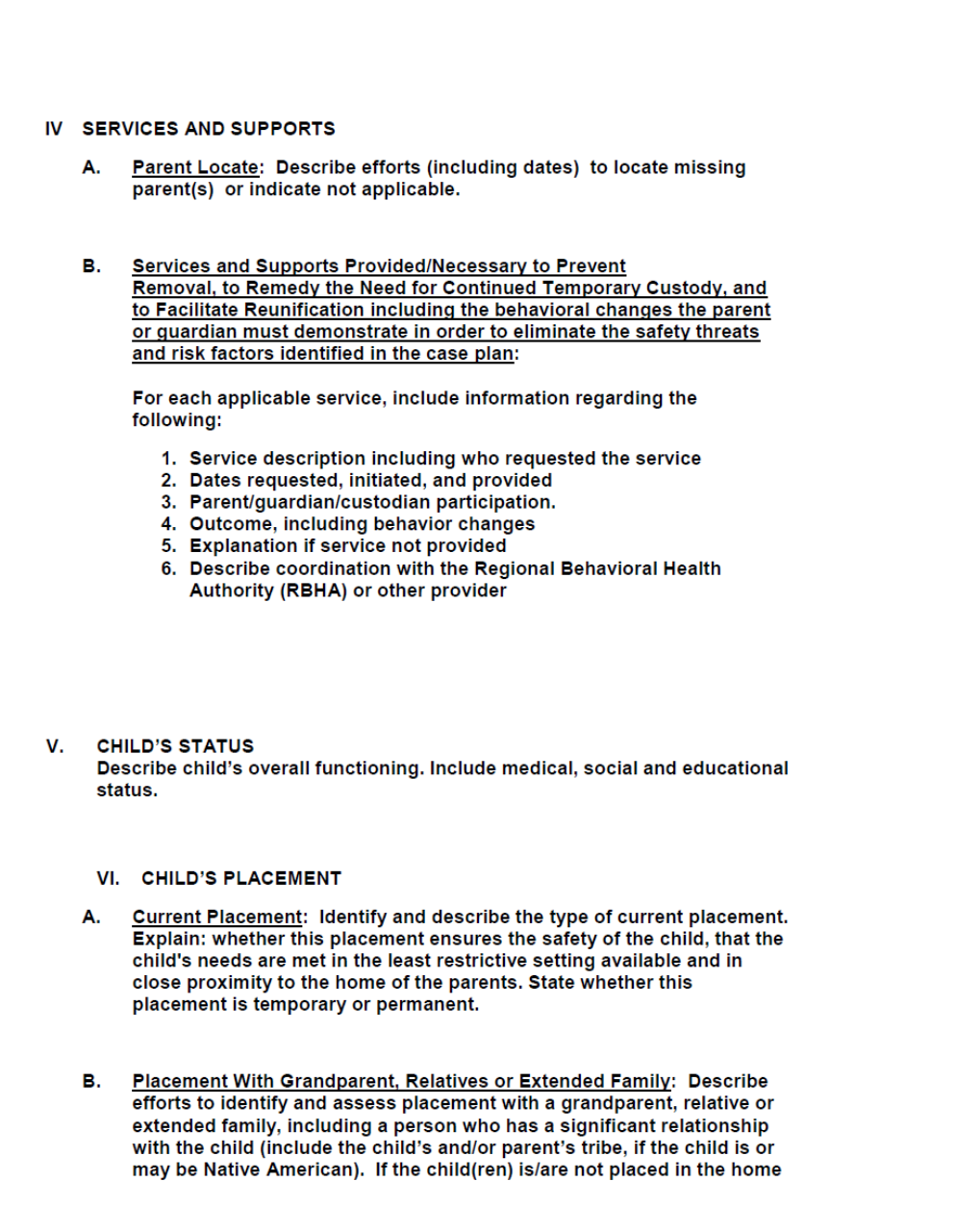

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I

PAGE

INTRODUCTION TO THE CLINIC

2

ABOUT THE HANDBOOK

6

GETTING STARTED

RULE 38 (D) AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPERVISING ATTORNEY

8

9

TEN RANDOM THOUGHTS ON GOOD LAWYERING

A LITTLE BIT ABOUT CHILD PROTECTION

DEPENDENCY PROCEEDINGS

11

14

15

THE PLAYERS

THE ROLE OF THE CHILD’S LAWYER

THE ROLE OF FEDERAL LAW

HOW A DEPENDENCY PROCEEDING GETS STARTED

DCS CRITERIA FOR RESPONDING TO A REPORT OF

MALTREATMENT

THE PPH PROCESS

THE COURSE OF A DEPENDENCY

CLINIC PROCEDURES FOR A NEW PPH

PPH FOR PRIVATE DEPENDENCIES

INDIAN CHILD WELFARE ACT

THE SETTLEMENT CONFERENCE

MEDIATION

20

25

44

46

49

52

66

69

101

104

111

120

DEPENDENCY ADJUDICATIONS

TOP TEN THINGS YOU OUGHT TO KNOW ABOUT EVIDENCE IN

JUVENILE COURT

DISPOSITION HEARINGS

DEPENDENCY REVIEWS

PERMANENCY HEARING

PERMANENT GUARDIANSHIPS

SEVERANCE PROCEEDINGS

ADOPTIONS

122

137

139

139

148

154

158

167

2

INTRODUCTION TO THE CLINIC

Welcome to the Child and Family Law Clinic. You are about to engage in a

unique and special learning experience -- one that will not only help you develop your

skills as a lawyer but will also challenge you to engage in a journey of self-discovery.

What is the Child and Family Law Clinic?

The Child and Family Law Clinic is a working law office in which law students are

the lawyers. The Arizona Supreme Court allows law students who have completed

three semesters of law school to represent persons in court under appropriate

supervision.

1

In the Clinic, students perform all aspects of that representation for our

clients.

We also believe that law practice is inherently multi-disciplinary. No legal

proceeding or contract negotiation or policy initiative is conducted in a law bubble.

There are always substance or evidence or policy considerations that are outside the

law. Lawyers regularly work with other professionals – accounting, medicine,

engineering, chemistry, psychology . . . It’s a pretty long list. Whether these other

professionals are clients, collaborators, advisors or expert witnesses, you will need to

develop your skills in working with other professionals in order to be a quality lawyer.

As our name suggests, our clients are mostly children who are involved in child

abuse and neglect (dependency) cases in the Pima County Juvenile Court.

Occasionally, we are asked by the Juvenile Court to represent parents as well -- usually

teen parents. And, once in a while, we asked by the Superior Court to represent

children in private custody disputes when there is an allegation of abuse or neglect. .

This semester, we may also interview and provide advice to adult victims of

intimate partner violence. This Handbook is about Dependencies. If we represent

victims of domestic violence, we will provide you all with other materials.

The Child and Family Law Clinic is assigned clients directly from the Courts. The

Clinic has a contract with Pima County to provide legal services to children and to a few

adults. In rare situations we might take a client on referral from another agency, but

only where there is a unique learning opportunity.

What is the Student’s Role in the Clinic?

The Child and Family Law Clinic is a live-client experience. By that, we mean

that you will be working with real people who have real legal problems. The clients will

be your clients and the cases will be your responsibility. We want you to make the key

lawyer decisions, choices, strategies and implementations in your case. We don’t

1

Rule 38, Arizona Rules of the Supreme Court. There are a number of other

conditions that apply including internal law school requirements.

3

want you to be the assistant to a more experienced lawyer; we want you to be the

lawyer.

Representing clients for the first time can be heady stuff. For some, it may be

exhilarating. For others, it may be frightening or unsettling. For some, it may be both

at the same time. We offer no predictions for you. We do, however, know that one of

the best ways to learn professionalism and good lawyer judgment is to practice them in

a setting that is designed for and focused on your learning.

That does not mean that you will be swimming alone. Quite the contrary, the

Clinic faculty and staff will be there with you to help prepare you, guide you, and offer

constructive feedback. We are a collaborative law office where all of us work together

for the benefit of our clients and for the professional development of our students and

ourselves. The bottom line, however, is that the final lawyer decisions are yours.

What makes the Clinic different from other courses?

First and foremost, your work is not theoretical or doctrinal. It is practical and

experiential. That does not mean that doctrine and theory are unimportant. In fact, the

opposite is true. We expect you to draw on all of your previous work in law school and

apply it in action on behalf of your clients.

One of the more exciting aspects of the Clinic is that it introduces you directly to

the lawyer-client relationship. You will represent clients and they will rely on you to

represent them well. Experiencing this reliance is the best way to appreciate the

implications of the role of a lawyer, the foundations of professional responsibility, and

the core values of the profession. You will need to draw on your previous law school

experience, your life experience, and your common sense to perform tasks well.

When someone is relying on you, you may face difficult strategic choices.

Sometimes you may face ethical or moral dilemmas. Your faculty supervisor and your

other clinical colleagues will help you make those choices for yourself.

Thus, a second obvious difference between the Clinic and most of your previous

courses is the relationship you will have with the faculty member who supervises you.

Even if you have worked closely with an attorney in an outside job, you will find that

there is a difference when the attorney with whom you are working makes what and

how you learn a high priority.

A Clinic course puts you in regular, sometimes daily, contact with a faculty

member. Much of the contact is spontaneous and informal. You may feel some

awkwardness about this relationship. We expect that. Nevertheless, be assertive and

take advantage of the Clinic faculty's presence. Clinic faculty are expected to be

accessible to you, but it is up to you to initiate the informal contact.

Third, in the Clinic, we work collaboratively. Because we represent real people,

we have to put their needs ahead of our egos. But isn’t that the task of a lawyer in any

4

event? No ego means there is no embarrassment. There are no dumb questions -- only

the questions we did not ask. We encourage a frank and honest exchange of views.

Only then can our clients be guaranteed the best legal services that we can offer.

With those considerations in mind, the Child and Family Law Clinic has four main

goals:

(1) Enhancing Lawyer Skills. Through practical experience in

the field and in classroom simulations, we want you to develop your skills

and learn a little about the law. You will have a chance to interview

clients and witnesses; to investigate facts; to research the law; to write

motions and court reports; to negotiate; and to stand up and advocate in a

real courtroom.

(2) Learning how to learn from experience. In addition to cultivating

lawyer skills, we want you to begin to master the lifelong skill of learning from

experience -- not only about the law, but also about yourselves. We hope that

we can help you help yourselves to become reflective lawyers – that is lawyers

who are not only highly skilled professionals, but who also care and think

about the quality of the justice, ethics, and morality of the profession.

(3) Developing good lawyer judgment. In the process of (1) and (2)

and drawing on lessons from all your other classes, we hope that your sense

of lawyer judgment will develop and mature. By “lawyer judgment” we mean

making the kinds of decisions -- both practical and ethical --that lawyers are

called upon to make regardless of their area of practice. We want to you make

decisions with a purpose and be true to the values of the profession and to

your own moral compass.

5

(4) Delivering high quality, purposeful, legal services. Finally, we

expect the Child and Family Law Clinic to provide the highest quality legal

services to our clients. Our clients deserve nothing less.

How do these goals affect you?

One result of all this is that you have an opportunity to shape the agenda for your

learning. A clinic is a more individualized learning experience than most other courses. As

with most things, you will get out of this experience what you put into it. You play the

primary role in establishing your working relationships within the Clinic. You have significant

control over the content of the learning within the context of the issues and tasks presented

by your cases. If you take the initiative, you can make this a great experience.

You have heard that in law school, you learn how to “think like a lawyer”. That is

certainly one of the goals of this clinic. But a clinic experience is about more than thinking.

We want you to explore how to act as a lawyer, how to make decisions as a lawyer, and

how to relate to clients as a lawyer.

In the Clinic, you will discover that there are aspects to thinking like a lawyer that are

not easily taught in other courses or contexts. When the decisions you make affect people’s

lives, they are different from the decisions you make in a classroom discussion or while

6

writing a paper. The decisions lawyers make come with real world responsibility. Making a

three foot putt in a tournament or playing an etude at a recital is a different experience than

doing the exact same thing in practice. We hope you can embrace the notion that your

decisions will matter.

Scary? Maybe a little. But we have all the confidence in the world that you are

ready.

Becoming accomplished in your new lawyer role will require you do things you may

never have done before, or, at least, require you to do them in a new context. For example,

you may have negotiated over many things in the past, but now you may have to negotiate

as an agent for your client, adding your special expertise as a lawyer. You may have

explored legal analysis of a problem with many hypothetical variations in which the facts

change each time. But here, you may have to discover and prove those facts. They may

not be so visible and accessible.

Newness is ok. We want you to stretch yourself, to take on new experiences, to take

a few risks. We want you to test yourself. And we also want you to recognize that it is just

as important that you learn to put these individual experiences in a broad context that will

make them useful and interesting over a long career. This will help you better appreciate

the lessons of your other law school courses.

Good luck. Work hard. Challenge yourself. Learn a lot. Oh, remember this as well,

have some fun while doing it.

ABOUT THE HANDBOOK

This handbook is an informal and somewhat unrefined reference work designed

to be a starting point for some of the problems that you will encounter. The handbook

contains chapters, training materials, and other materials gleaned (or stolen outright)

from various child- advocacy and child-welfare sources.

While the handbook contains a wealth of materials, it is not designed to be an

answer manual for all of your questions. Nor is the handbook the last word on any

subject. The handbook will NEVER be a substitute for proper research. The handbook

should be used as a starting point only. Nonetheless, we hope the handbook will be a

useful tool in helping to get you started.

The Clinic handbook contains four types of materials. The first type sets out the

basics of dependencies, severance, and guardianships. Included are statutory and

case references. Again, these articles are not ultimate truth, but should provide an

overview. Always check out the current statute or rule. Laws change.

Sometimes overnight – and without much fanfare.

The second type of material provides a how-to commentary or practical

background information about a particular aspect of a juvenile case.

7

The third type of material is an Appendix, which includes examples of minute

entries, common pleadings, letters, and other documents with which you may come in

contact. In the law library of nearly every law office, you will find some compilation of

these documents in the “form drawer” or the “form file”.

Here are our thoughts about “forms”. Forms are provided for examples

only. Forms are not a substitute for thinking. Remember, “form” is a four letter

word beginning with “F” and we should always be careful of such words. Our

examples are for guidance not for gospel. Never rely on someone else’s form or

someone else’s words for content. Every letter or pleading you prepare should be the

result of YOUR well planned thoughts for your particular task. One size rarely fits all.

Finally, we have included references to relevant statutes and rules throughout

the Handbook. They are hyperlinked. Nevertheless, remember, statutes get revised

more quickly than the handbook. Check the pocket parts or on-line to make sure

that your version is the current version.

One final, final note: the handbook is always a work in progress. If you have any

suggestions, additions, corrections, or proposed deletions, please feel free to talk to the

Clinic Director. If you work on an interesting case and would like to add a form [oops,

there we said it], pleading, or your own insight, please do not hesitate to come forward.

8

Getting Started

At first, the child protection system will seem to be a very confusing and

cumbersome collection of courts, governmental agencies, and private entities -- both

non-profit and for profit. There are a host of different players in the system with different

titles and different roles. There is no shortage of agencies with a plethora of acronyms.

2

It will sometimes appear as if people in the system are speaking a foreign language -

- at least as foreign as the language of lawyers must seem to the justice-consuming

public.

Part of your job will be to learn the language of child protection just as you are

learning the language of the law. You need to understand child-protection talk so that

you can properly represent your clients with these agencies and in court. You also

need to be able to translate for your clients so that they can make intelligent decisions in

their own best interests. We hope this handbook will provide a healthy starting point.

The good news is that we have every confidence that you will master the terrain

and the language of child protection. In many ways, the child protection community is

peopled by a remarkable collection of individuals extremely dedicated to helping

children. There is a lot to be learned from most of the people in the child-protective

system. And most of them are more than happy to assist you in any way they can.

So, our first piece of advice is simple: Go slowly. Take your time and, above all,

ASK QUESTIONS. If you don’t understand something, ask about it. If you hear a new

phrase or acronym, ask what it means. One of the first steps in learning how to

learn from experience is learning how to ask questions.

You will be encountering some experiences that are new to you -- whether they

are speaking in court, writing a motion or interviewing a child. It may seem like you are

leaping off a cliff with no knowledge of how to fly. And while we want you to stretch

yourselves, remember that you are not alone. Don’t try to be the Lone Ranger. We are

a team -- a team that includes your supervising attorney, your clinic partner, your social

work intern, and the rest of the members of the Clinic.

Our second bit of advice is just as simple as the first. Talk to each other. Don’t

be afraid to ask for help. Share your problems and experiences with the other

members of the Clinic team. Brainstorm with other Clinic students. Knock on your

supervisor’s door. Use what others have learned to help you to solve problems. Use

the team.

Third, despite all the lawyer jokes, we know full well that lawyers have feelings,

too. In the course of representing your clients, you will undoubtedly be exposed to some

of the darker sides of life -- drug-abusing parents who don’t seem to care about their

children; angry or frightened children who don’t seem to be able to negotiate the world

2

A list of common acronyms is included in the Appendix

9

into which they have been thrust; agency personnel who don’t seem to have the time,

energy, or resources to do their jobs properly.

It is not easy to watch other people’s difficulties -- particularly those of children. It

will be especially frustrating to realize that, as a child’s lawyer, you cannot fix

everything. It may be even more difficult if your client’s situation evokes something

personal in you. It is perfectly normal to experience anger, frustration, or sadness at

what you observe.

While we cannot tell you how to feel, we can tell you that it is important to

recognize your feelings and to deal with the fact that they exist. Share them with others

if you feel comfortable doing so; if you don’t, keep a journal or diary. Whatever you do,

try to be reflective about how the experience of representing children affects you.

Learning to reflect is one great and important step in learning how to learn

from experience. It is central to what we are trying to accomplish in the Clinic.

RULE 38 (D) AND THE ROLE OF THE SUPERVISING

ATTORNEY

As law students, you are allowed to practice law under Arizona Supreme Court

rule 38(d). Under the rule, you are called a “certified limited practice student”

3

. [We

didn’t make that up]. Get used to the phrase “certified limited practice student” --

you’ll be using it a lot and it is a mouthful. Go ahead. Try it out loud. In front of a mirror:

“My name is _____. I am appearing as a certified limited practice student

on behalf of _____.”

As a certified limited practice student, you will be given primary responsibility for

your cases. You meet with your client. You gather information. You marshal evidence.

You appear in court. You make the arguments. You do the negotiations. You make

the decisions. These are your cases.

BUT, you are not alone. Your supervising attorney is there to help. Your

supervising attorney will help you plan, will be with you in court, will review your legal

writing, and will offer you feedback. It is the supervisor’s role not only to assist you to

perform your job well but to help you learn from your experiences in the Clinic.

You will also be practicing in an area of law that requires you to interact with

human services agencies of all shapes and colors. Take advantage of the offers of

help. Hopefully, you, your clinic partner, and your faculty supervisor will develop

healthy, professional relationships. Don’t be shy.

3

Rule 38, AZ Rules of the Supreme Court.

10

A small note of self interest. It is also your supervising attorney’s law license

that is on the line whenever you act as a certified limited practice student. Your

supervising attorney has more than a passing interest in making sure that you are the

best lawyer you can be for your client. Make sure that you keep your faculty supervisor

well informed about what is happening in your cases so that the supervisor’s ulcers will

be kept in check. So:

1. Make sure that you meet regularly with you Faculty Supervisor.

2. Check your mail box and email frequently for messages.

3. Be in the Clinic during your office hours.

4. Meet with your supervisor before and after all significant case events.

5. Before you send something in writing (including email) out the door,

show it to your faculty supervisor.

6. Keep your files up to date.

7. ASK QUESTIONS!!

11

TEN RANDOM THOUGHTS ON GOOD LAWYERING

Before getting into the basics of dependency law, we thought we would share a

couple of thoughts about being a lawyer in the Juvenile Court. We often say that being

a lawyer in Juvenile Court is like being a lawyer in any other trial court -- except more

so. Accordingly, the following thoughts apply to all courts, but apply especially in the

Juvenile Court. These thoughts are in no special order but can be useful aphorisms to

get you going in the Clinic and are somewhat reflective of our general philosophy.

1. Learn to Listen

Listening, really listening, is one of the most useful and important skills that a

lawyer can develop. Listening means not just hearing the words but getting the actual

and hidden meanings behind what someone else is saying. Listening takes

concentration and can be hard work. But it is work that will be well rewarded.

Listening means getting to know the person with whom you are talking. This is

especially true with child clients. Get to know them in the context of their own lives.

Then you can really hear what they say.

Listening will help you understand what your clients really want. Listening will

help you see where a Judge may be leaning. Listening will help you interview

effectively. Listening will help you see if there is common ground for compromise.

Listening is a skill -- like playing piano, swimming, or painting portraits. Like all skills,

listening needs to be practiced and cultivated. Work at your listening skills. They will be

well worth it.

12

2. Courtroom style is way overrated; clarity is not.

In Court, all other things being equal, the better prepared lawyer will get better

results. The flashy lawyer, without quality preparation, doesn’t get much of anything.

If you think about it for just a moment, it is easy to see that the Judge in

Juvenile Court is far more concerned with making the correct decision about a child

than in evaluating the performance of the lawyers -- you included. Whether or not a

lawyer looks nervous or stutters or is not smooth takes a far distant second place to

clear communication and making the right decision for a child.

So what helps Judges make the correct decision? Presenting all the relevant

facts; answering all their questions; having presenting argument in a clear, lucid, and

digestible fashion. It does not take Clarence Darrow to present a case in Juvenile

Court. It does, however, take hard work and quality preparation.

That is why the Clinic has been successful for our clients. We work hard. We

gather all the relevant information. We are on top of things. Our preparation helps us

assist the Judge in seeing our client’s point of view. Style points do not count;

preparation does.

3. Judges are busy; make their jobs easier

Be concise. Keep it simple. Get to the point quickly. While style points don’t

count, it is still important to be a good communicator. We don’t need to look flashy, but

it is essential that we get our point across within the limited time allotted.

How do you do that? Prepare, prepare, prepare. Think about what you want to

convey to the Court in advance -- and work on it. Don’t assume that the Judge knows

everything you know but make sure that you don’t waste time on matters about which

the Judge is fully informed. Put yourself in the Judge’s shoes and ask yourself the

following: “What would help me make a better decision?” Then, provide that.

13

4. Planning is everything; reflection is learning

Everything we do -- whether it is interviewing our clients, telephoning a case

manager, talking to a doctor, or advocating in court -- will go much more productively if

we plan before and reflect after. Be a purposeful lawyer. Try these four simple steps:

Step (1) Before undertaking any task, ask and answer the following

question: “What am I trying to accomplish?” Then, define your actions

and goals according to the answer.

Step (2) Review your plans and ask yourself: “Will this help accomplish

my goal?” If you are still on track, go for it. If not, revise your plans.

Step (3) Once you’ve completed your task, ask yourself the following:

“Did I accomplish what I set out to do? Why or why not?” File that

answer under “Something useful that I learned today”. Don’t forget this

step. This is where real learning takes place.

Step (4) After completing the first three steps, ask yourself the “big picture”

question: “What did I learn today that will help me as a person and as

a lawyer?” This step is where real insight takes place.

5. Do not underestimate the power of the written word

Getting information to a Judge in a form designed to communicate your position

is one of the main tools of good lawyering. Advance written reports and motions can be

extremely effective communication media. In Court, Judges have only a few moments

to make decisions; there is little time for a Judge to ponder the finer points of the law.

Judges are fully aware that rushed decisions are never the best decisions. By

offering quality written work in advance of the hearing, we give the Judge time to

decide. The more time a Judge has to think through the correct decision, the more

likely it is that the Judge will make that decision correctly. Likewise, the more time the

Judge has to think about our arguments, the more likely the Judge will be to understand

and accept them.

As a corollary, never underestimate the power of advance notice: Be heard first.

A well written report, motion, or brief helps to focus the argument where you want it

focused. Judges may not always accept what you want them to accept, but if you can

get them thinking about it early, you have a better chance of being successful.

6. You cannot speak too slowly in Court

Speaking too quickly is like bad handwriting. It is an unnecessary obstacle. If

your Judge cannot follow your argument, you will not have much impact. If you speak

too quickly, it is a guarantee that your argument will not be followed.

14

In court, your adrenalin pumps. Your heart beats 1,000 times per minute. You

lose your sense of time. Time seems move more quickly than it actually does. So take

the time to take time. Slow down. Take a deep breath. Pause. No matter how slowly

you think you are talking, talk even more slowly. Speak up. Slow down. Then you can

be understood.

7. Write it down

Whenever you do anything on a case, write it down NOW. Make an immediate

record and put it in the file. None of us can remember everything accurately. However,

we are more likely to remember it if we make a contemporaneous record. As Stephen

Wright says, “Everyone has a photographic memory, some just don't have film.”

8. Return all phone calls promptly

Nothing irritates people more than not getting return phone calls. And little

pleases more than a promptly returned phone call. The consequence of each choice is

obvious.

9. Silence is golden

Keep your client’s secrets. Confidentiality goes to the heart of the lawyer-client

relationship. That relationship is about trust. It is exciting to talk about your cases. But

there is a client at the heart of every conversation who deserves his or her privacy.

10. Keep your client informed

We will often have a lot more information about our cases than our clients will

have. If your clients are old enough or mature enough to understand what is going on,

keep them as well informed as possible. It is, after all, their lives. They have a right to

know what is happening around them. They also have the right to the information they

need to make intelligent choices about their lives.

How many lawyers does it take to change a light bulb? None. Lawyers like to

keep their clients in the dark.

10 1/2. Life is Short. Have Some Fun

15

A LITTLE BIT ABOUT CHILD PROTECTION

The legal protection of children is a relatively recent phenomenon. Historically,

children were considered chattel. The State did not interfere with the manner in which

parents raised their children in the same way that the State did not care how parents treated

their furniture. The State’s only involvement was in caring for orphans who had no relatives

to care for them.

As late 1970, many states had no laws whatsoever dealing with child abuse. In cases

of severe abuse, such as broken bone beatings or whippings, the states had to protect

children under animal cruelty laws. Even into the early 1970's, most states’ responses to

child abuse were limited to criminal prosecutions of only the most serious cases.

In the early 1970's, two parallel trends began to emerge. Congress began to provide

money to the states to investigate child abuse and neglect. In addition, Congress allocated

money to help states remove abused and neglected children from their homes, care for

those children in foster care, and provide remedial services to help reunify families.

Around the same time, many states passed laws creating a civil child protection

system. Laws were enacted providing a mechanism for a state’s response to allegations of

abuse and neglect. Juvenile and Family Courts were established in recognition of the

special expertise necessary to make complicated child-protection decisions.

In the last 25 years, the child protection system has grown enormously as societal

attitudes about the role of government in protecting children have changed. Every state has

a hotline through which citizens can telephone anonymously to report cases of abuse or

neglect. Most states mandate that certain professionals such as doctors, nurses, teachers,

and therapists report suspected cases of child abuse.

Over the years, concepts of abuse and neglect expanded to include more than

severe beatings or the failure to feed children. They now include emotional neglect, chronic

unsanitary conditions, and parental substance abuse. The bureaucracy necessary to

administer this system has also expanded as literally thousands of children became wards

of the state. The latest report shows nearly 16,000 children in foster care in Arizona alone.

4

With the growth of the child-protection industry, controls were necessary to ensure

that children had adequate protection from the bureaucracy as well as from their parents.

Courts became more vigilant in monitoring the status of children in state care. Children,

themselves, were assigned lawyers or guardians ad litem to look out for their interests.

While different states approach abuse or neglect differently, the Federal government

maintains an enormous influence on the nature of child protection. In a later section, the

handbook will look at the current role of Federal involvement in setting standards. Our first

section deals with the basic concept of dependency.

4

Child Welfare in Arizona Semi-Annual Report Update June 13, 2014, page 4.

16

DEPENDENCY PROCEEDINGS

What is a dependency?

A dependency proceeding is a formal court process to determine if a child’s well-

being requires the state to intervene in the parent-child relationship.

5

The proceeding

determines whether or not the child is dependent on the state to provide parental care

because of the parents’ inability or unwillingness to provide proper and effective care and

control.

6

A child may be dependent on the state because the child has been abused or

neglected or because the child is at risk for abuse or neglect in the imminent future.

7

Dependency is a somewhat broader concept than abuse or neglect and does not

necessarily imply that the parent is at fault or has committed some kind of wrongful act. For

example a parent may be ill or under some disability and unable to care for a child. Thus,

the focus of a dependency proceeding is on the capacity of the parent -- not just the parent’s

motives. There is really only one question: Does the child have a parent who can

provide minimally adequate parental care or does the state have to step in? Thus, for

example, a mentally retarded parent who would never harm a child or deliberately neglect a

child might nevertheless be considered incapable of caring for a child faced with a life

threatening disease which requires specialized training to monitor.

In other states, a dependency proceeding might be called a “child protective

proceeding” or a “child abuse and neglect” proceeding. The distinction is important

because the Arizona definition of dependency is significantly more inclusive than some

traditional notions of child abuse and neglect.

8

Dependency proceedings in Arizona are heard exclusively in the Juvenile Court.

9

5

ARS §§ 8-201(14); 8-801, et seq. children are raised by their birth parents. For our purposes,

we will use the term “parent” to mean birth parent, adoptive parent, guardian or some

other legal custodian. We will use the term “parent” to mean the person who is legally

raising the child.

6

ARS § 8-201(14)

7

Thus the State does not have to wait until the child is actually hurt to step in. If a parent is a

demonstrable crack cocaine addict, for example, the state does not have to wait until that parent

causes actual harm to the child in order to act.

8

Different states approach this problem in different ways. New York and Pennsylvania, for

example, utilize the concept of “abused or neglected child” rather than the notion of dependency.

The focus in those states is whether the child has been harmed or is in imminent danger of being

harm. There are some subtle advantages and disadvantages to the more parent-focused

dependencies versus the more child-focused definitions of an abused or neglected child. The

growing case law in both types of jurisdictions, however, appears to be making the distinctions

nominal at best.

9

ARS§8-202(B)

17

While Juvenile Court is, technically, a part of the Superior Court, the Pima County Juvenile

Court is housed in a separate building on Ajo Way near Kino Hospital (now called UMC

South). Throughout the state, the Juvenile Court operates under a different set of rules and

procedures than those used in other civil proceedings. Juvenile Court also has its own

culture or way of doing things that is less formal and, in many ways, more innovative than

that of other courts.

In theory, the Juvenile Court is not in the business of finding fault, assessing blame,

or meting out punishment. Rather, the Juvenile Court is interested s in protecting the child

from immediate harm and in providing the services necessary to help preserve the family.

If efforts to help make the family functional do not succeed, then the Juvenile Court is

empowered to find an alternative permanent and safe home for the child.

10

We say that the Court is not about parental fault. That is certainly true under the law.

However, the dependency process is a terrifically human. While the law may say otherwise,

in actual practice fault, blame, shame, attitude, and a host of other technically irrelevant

considerations play a huge role in determining what will or will not happen to a child in the

court process. None of the participants -- including the Judges, case managers, therapists,

and lawyers -- are immune from visceral reactions to parental behavior. That will, no doubt,

include you as well.

Dependency proceedings are usually initiated by the State through the Arizona

Department of Child Safety [DCS ].

11

Up until this past May, the Department of Economic

Security [DES] through Child Protective Services [DCS] handled child protection matters.

Because of a variety of factors, the Governor and State Legislature abolished DCS and

created the new agency, DCS .

12

If that isn’t confusing enough, people have been calling

the agency DCS for the last 30 years. It will be a hard habit to break. So, for the

foreseeable future, CPS and DCS are acronyms that refer to the same folks. In Juvenile

Court, DCS is represented by the Arizona Attorney General’s Office [the AG].

In Arizona, a dependent child is a person less than 18 years old who is:

(i) In need of proper and effective parental care and control and who has no

parent or guardian, or one who has no parent or guardian willing to exercise or

capable of exercising such care and control.

(ii) Destitute or who is not provided with the necessities of life, including

adequate food, clothing, shelter or medical care, or whose home is unfit by

10

ARS §8-862

11

Congratulations, you have now learned your first acronym!! There are many more to come.

Arizona law also provides that private individuals can initiate dependency proceedings (ARS §8-

841).

12

http://www.azcentral.com/ic/pdf/brewer-DCS-executive-order.pdf

18

reason of abuse, neglect, cruelty or depravity by a parent, a guardian, or any

other person having custody or care of child.

(iii) A child whose home is unfit by reason of abuse, neglect, cruelty or

depravity by a parent, a guardian or any other person having custody or care

of the child.

13

Thus, dependencies include traditional concepts of abuse and neglect, such as

excessive corporal punishment or failure to provide medical care. Dependencies may also

include less clear-cut notions of “risk”. For example, a child might be “at risk” of neglect

from a parent who -- although adequately caring for the child today -- is becoming

increasingly dependent on drugs or alcohol and whose long term capabilities are in doubt.

Similarly, a child might be at risk of long term psychological harm when the child has been

exposed to domestic violence in the household -- even when the violence is not directed at

the child.

14

To some extent, dependency may also relate to the particular needs of the child

rather than to the conduct of the parent. A dependency has been found where a child has

cerebral palsy and the parent, while capable of providing care for a healthy child, had

difficulty managing the child’s special needs.

One of the difficult aspects of practicing dependency law is that you will not find a

further definition of “dependent child” in the statutes. Trial Courts rarely publish their

decisions. And when decisions are appealed, the appellate courts grant broad discretion to

Juvenile Court Judges. It is, therefore, imperative that a juvenile court lawyer get to know

the lay of the land of the jurisdiction in which lawyer practices. Situations that may result in

dependency adjudications in one venue may be dismissed as insufficient in others.

What does it mean when a child has been adjudicated dependent?

Essentially, it means that the State may intervene to provide protection to the child

and/or services to the child and the family in order to try to remedy the problems that caused

the dependency in the first place. In practical terms, a number of outcomes can result. The

child could remain in the home or the child could be removed temporarily, for a long time, or

in some cases, permanently.

15

13

ARS §8-201(14). The statute further defines a dependent child as one who is (a)(iii) Under the

age of eight years and who is found to have committed an act that would result in adjudication as

a delinquent juvenile or incorrigible child if committed by an older juvenile or child and (iv)

Incompetent or not restorable to competency and who is alleged to have committed a serious

offense as defined in§13-604.

14

See, Adrine, Donald B. and Alexandria M. Ruden, Impact of Domestic Violence on Children,

OHIO DOMESTIC VIOLENCE LAW TREATISE, Ch. 14 (2000); and Ver Steegh, Nancy, The Silent

Victims: Children and Domestic Violence, 26 WM.MITCHELL L.REV 775 (2000).

15

ARS §8-821, §8-822, §8-845

19

If the child stays at home, the case could remain monitored by the Juvenile Court for

a time or dismissed outright. In either case, the State might provide services to support and

strengthen the family.

16

If the child is removed from the home, the child will be placed in

foster care or with a relative.

17

In addition, under court supervision, the State must develop

an appropriate individualized case plan to ensure the child’s health and safety and to

attempt to reunify the family.

18

The case plan should be designed to provide the assistance

necessary to alleviate the problems that gave rise to the dependency in the first place. In

most instances, if the parent follows and completes the case plan, the child will be

returned to the parent.

Removing a child from his or her family is serious business. Even when removal is

clearly warranted to protect the child’s physical safety, being taken from home can have

huge negative consequences for a child. Separation -- even from abusive parents -- is

traumatic. In addition, the child may be separated from brothers and sisters, forced to

change schools, isolated from friends and relatives, or placed in unfamiliar and often scary

surroundings. For an infant child, separation may impede or even forever destroy the natural

bonding and attachment process between parent and child.

Separation is no less difficult for a parent. In addition to the emotional shock of losing

one’s child, a parent may become ostracized by his or her family, stigmatized by neighbors,

or may lose eligibility for child support, government subsidies and public housing. Further,

in order to reunite with the children, a parent may be forced to navigate a child protective

bureaucracy that is often confusing, contradictory, and speaks an alien language. Many

times, completing a case plan is a task for which many sincere and well-meaning parents

are ill equipped.

Thus, continued visitation, good communication, and an intelligent case plan are

necessary to maximize the chances for successful reunification. The attorneys for the child,

the parents, and the State play key roles in this process.

Of course, whether or not a child is adjudicated dependent is subject to full court

process. Parents have significant rights to raise their children free from interference from

the State. Parents have a right to Court review of temporary decisions as well as the right to

a trial on the substantive allegations of dependency and on any proposed dispositions. That

process will be discussed in later sections of this handbook.

16

ARS §8-845, §8-846

17

ARS§8-821, §8-501; Foster home is defined in ARS §8-501 as a home maintained by any

individual(s) having the care or control of minor children other than those related by blood or

marriage. Foster homes are licensed and supervised by the state pursuant to ARS §8-516.

Relative placement may be ordered by the court even if the relatives are not licensed foster

placements. Relative placements may be eligible for state foster care payments. Even though

the placement is with a relative --which potentially minimizes disruption of the child’s life -- the

court will require the relative to obey the court orders regarding such things as visitation between

the parent and the child.

18

ARS §8-846

20

When a child is declared dependent and removed from the home, in nearly all cases,

the State is obligated to make “reasonable efforts” to help reunify the family.

19

These

efforts may include supervised visits, transportation, psychological testing and counseling

services, medical assistance, drug or alcohol monitoring and treatment, parental education,

job training, housing subsidies, or any number of other services that would help put the

family back together.

20

In many cases, parents and children are reunited with help from the Courts, the State

and other family members. In other cases, things do not proceed so smoothly. The current

reunification rate in Pima County is 49%. That means that about on half of all children

removed from their homes are returned. The other half will face a different path.

In some situations, such as severe child sexual abuse or acute drug addiction,

reunification is simply not a reasonable alternative. In others, for a variety of reasons, the

parent or guardian will be unable to remedy the conditions that caused the dependency in

the first instance within the time prescribed by law. The Court, then, is obliged to find a

permanent placement for the child either through adoption, permanent guardianship

with a relative or other appropriate person, or long term care consistent with the child’s best

interests. Long term care is called “Another Planned Permanent Living Arrangement” or

APPLA. There is a decided preference for adoption or guardianship over long-term

foster or relative care under Federal and State law.

In any event, whether or not progress is being made towards reunification, if a child

remains placed out of the parent’s home for twelve months [or for six months for a child

under 3], the Juvenile Court must hold a permanency hearing to determine a long term

plan for the child.

21

At a permanency hearing, the Judge must choose among the possible

permanent plans for the child. The permanent plan may involve returning the child;

continued reunification services for an additional six months; discontinuing reunification

services and placing the child in some other planned permanent arrangement [usually long-

term foster care]; seeking a permanent guardianship; or seeking permanent termination

of parental rights and freeing the child for adoption.

22

If, by the time of the permanency hearing, the parent is unable or unwilling to

complete the case plan and/or is unable or unwilling to remedy the problems that caused the

child’s removal, then the State may seek permanent termination of the parent’s rights. The

Juvenile Court refers to a permanent termination of parental rights as a severance.

23

In a severance proceeding, the State must not only prove certain specified statutory

grounds for termination, but also show that termination of parental rights is in the child’s

19

ARS §8-846 In other parts of the law the phrase “diligent and appropriate” efforts is used.

More on that later.

20

ARS §8-846

21

ARS §8-861, §8-862

22

ARS §8-862

23

ARS §8-531,et seq.

21

best interests.

24

In most cases where the parent’s rights are terminated, the State will seek

to place the child for adoption. In some cases, when reunification is not likely but when

termination is not in the child’s best interests and someone (usually another family member)

is willing to take permanent care of the child, the State may seek permanent guardianship

with the relative.

25

In the next several sections, we will discuss the dependency process in more detail.

The discussion will emphasize the critical role of the child’s attorney in helping to make the

process work. While this manual is designed to focus on the practical aspects of Juvenile

Court, keep in mind that there are a number of difficult philosophical and ideological themes

that challenge all the participants in the process.

THE PLAYERS

There are a number of important players in the child protective system. You, as the

child’s attorney, are one of the most important. Others include the Judge, the DCS Case

Manager, the Attorney General, the parents, the parents’ attorneys, Court Appointed Special

Advocates (CASA), Guardians Ad Litem, Court clerks, Court Reporters, court mediators,

and a host of others. The following is a list of some of the participants and their roles. As

you read through the handbook, feel free to come back and review this collection of people.

The Child

The child is the center of the whole process. The court has jurisdiction over children

from birth until age 18. Because the child is a child, adults, sometimes, do not listen to the

voice of that child. When the adults don’t listen, it is our job to make sure that the child and

the child’s legal interests are heard by the people that need to listen.

The Parent

The parent is the birth parent and/or any other lawful custodian. The parent can be

an adoptive parent, a legal guardian, a non-custodial parent, a grandparent or other relative

under some circumstances. There may be many parents involved in one of our cases. For

example, siblings might have a different father [or mother]. In most cases, the parent will be

the legal parent [the birth or adoptive parent] and/or the person who was taking care of the

child at the time DCS got involved if someone other than the birth or adoptive parent.

Families come in all shapes and sizes.

The Judge

Pretty much everything in the child protective system revolves around the Juvenile

Court Judge. Judges are charged with the ultimate responsibility for decisions concerning

24

ARS §8-533

25

ARS §8-862B and§8-871, et seq.

22

the lives of children who are before the court. There are no juries in the Juvenile Court.

26

The Judge is the final word on both the law and facts in every case.

There are two kinds of Judges in the Pima County Juvenile Court. There are

Superior Court Judges who are appointed by the Governor for fixed terms. At the end of

their term, they must stand for a retention election. A retention is an up or down vote by the

electorate with no opposition candidate. There are also Commissioners who are appointed

by the Presiding Judge of the Pima County Superior Court. Commissioners serve at the will

of the Presiding Judge.

In Juvenile Court, both types of Judges have the same responsibilities and powers

and are due the same respect. Any differences between Judges and Commissioners are

internal to the Court and rarely affect us -- except that Judges get law clerks and often hire

our students to fill those jobs. Exposure to Judges can be an unintended career perk for

some of you.

The Judges are assigned to the Juvenile Court by the Chief Judge usually on a three-

to five- year rotation. The Chief Judge controls the rotation and also appoints a presiding

Judge who is in charge of the administrative operations of the Juvenile Court. Currently the

presiding Judge of Juvenile Court is Kathleen Quigley. The other Judges and

Commissioners are:

Hon. Lisa Abrams

Hon. Jane Butler

Hon. Michael Butler

Hon. Julia Connors

Hon. Geoffrey Ferlan

Hon. Richard Gordon

Hon. Susan Kettlewell

Hon. Jennifer Langford

Hon. Brendan Griffen

Hon. K.C. Stanford

Hon. Catherine Woods

Hon. Wayne Yehling

26

There were jury trials for about three years in the early 2000’s. Parents could request a jury trial for

a petition to terminate parental rights. Apparently the only people who liked jury trials were some

parents and clinical professors. (We thought it was cool to have you doing jury trials). So the

Legislature went back to the Judge only system.

23

The Judges in the Juvenile Court work extremely hard. The Pima County Juvenile

Court is nationally recognized as one of the more innovative, responsive and hard-working

Juvenile Courts in the nation.

As you will quickly learn, a Judge’s day is made up of non-stop hearings, with very

little down time to prepare for the next case. As a result, Judges rely heavily on the

participants to bring them up to speed. Traditionally, Judges have relied on written reports

from DCS workers. But that does not always tell the whole story. (It is, after all, an

adversary system). For that reason, we encourage you, as the child’s attorney, to submit

written reports to ensure that the Judge is as fully informed as possible about the child’s

interests and needs.

All of the Judges have Chambers in the Juvenile Court Building at 2225 E. Ajo Way,

Tucson, AZ 85713. The main telephone number for the court is 740 -2000. The individual

Judges’ telephones are listed in the Blue pages of the phone book under Pima County

Juvenile Court and on the Pima County Superior Court website.

http://www.sc.pima.gov/?tabid=103

Case Managers

The Child Protective Services workers assigned to each family are called Case

Managers. There are two principal types of case managers: investigating workers and on-

going case managers.

As their name suggests, the investigating workers are responsible for the initial

response to an allegation of abuse or neglect. The investigating workers make a

determination whether or not there is credible evidence to make an administrative finding of

abuse or neglect. With help, they decide whether or not to remove a child from the parents.

They prepare an initial report to the Juvenile Court, notifying parents of their rights, and

develop and implement an initial case map

27

.

Once the matter has been brought to the Court, the investigating worker is

supplanted by the on-going case manager. The on-going worker is responsible for

developing the long- term case plan, for setting up therapy or other services, for working

with the parents to help them meet the case plan goals, and for communicating with the

Court.

In addition, both the investigator and the on-going workers are responsible for

providing disclosure to the other participants in the Juvenile Court processCthat is, for

making sure that the information gathered by DCS is made available to all the litigants.

Disclosure might include reports of drug tests, police reports, reports of therapists,

psychological evaluations, and other communications that are sent to DCS. Case Managers

are grouped geographically throughout the County in various units. The addresses and

27

A case map is a preliminary plan of reunification services.

24

phone numbers are listed in our course materials. You will also periodically receive e-mail

attachments with updated names, addresses and phone numbers of DCS workers.

We receive most of our disclosure through our mail box at the Juvenile Court.

Our mail box is in the attorney room as the far west side of the first floor. The boxes

are alphabetical. We are under “Bennett/child and family”.

A note of caution: There are behaviors we cannot control. One is the knee-

jerk insistence by some case managers to place our disclosures in the bin for the

Office of Children’s Counsel (OCC). The Office of Children’s Counsel represents the

vast majority of children in Juvenile Court – but not all of them. If there is something

you are waiting for – and it is not in our box – check with someone from OCC to see if

they received it by mistake. It happens way too often.

Two other notes of caution: DCS is represented in a dependency by the Office of

the Attorney General. Since the case managers are the contact persons for DCS, they are

technically “parties represented by counsel” in the dependency proceeding. As such, we

are not allowed to communicate with them absent their attorney’s permission pursuant to

Rule 4.2 of the AZ Rules of Professional Conduct.

28

Lately, the Attorney General’s Office

has become less comfortable allowing us – or any other lawyer – to communicate directly

with their client for anything other than the most minor pieces of information. For example,

it’s probably ok to send an email asking for the date and time of a Child and Family Team

meeting with a copy to the AG. It’s probably not ok to send an email asking the case

manager to reconsider visitation supervision.

Thus, whenever you want to speak to a DCS employee, go through the

Assistant Attorney General assigned to the case. It’s a pain but it is the best way to

avoid Bar complaints. This also means that if you plan on attending a Child and Family

Team meeting [CFT] or some other situation where DCS workers are present without their

lawyer, make sure that you notify the AAG, in advance, that you will be attending.

Second, DCS is undergoing a severe budget crunch. They do not have enough case

managers. They do not have enough resources to do their job as they would wish. That

creates an extremely uncomfortable situation. The workers are overworked, underpaid, and

cannot access the services they probably know would be most optimal. They have been

instructed to be somewhat minimalistic in their approach. They often have to say “no” when

they wish they could say “yes.”

We can and should be sympathetic with the difficult position of the individual case

manager. Nonetheless, we have a job to do – making sure our kids are well cared for,

28

“

In representing a client, a lawyer shall not communicate about the subject of the representation

with a party the lawyer knows to be represented by another lawyer in the matter, unless the lawyer

has the consent of the other lawyer or is authorized by law to do so.”

ER 4.2 is found within Rule 42 AZ Rules of the Supreme Court. In the remainder of the handbook,

we will cite the ethical rules as ER ___.

25

getting the services they need. And that our client’s goals – whatever they may be – have a

fair chance of being reached. That puts us in an increasingly adversarial position with DCS.

Adversarial positions are not, however, best served by being needlessly

confrontational or rude. We should always try working cooperatively when possible.

Sometimes it is not possible and we need to resolve differences in court. But we should

never be impolite or uncivil; nor should we make differences personal.

The Attorney General

In Arizona, the Office of the Attorney General represents the Department of

Economic Security [DES] and it’s Division of Child Protective Services [DCS]. The AG’s

office prepares dependency petitions, severance motions, and other court pleadings. In

addition, the AG’s office advocates for DCS both in and out of court in the same manner as

any other lawyer would advocate for any other client.

Over the years, we have developed a very positive working relationship with the AG’s

Office -- even though we often oppose each other’s positions in court. One of the more

remarkable aspects of the Juvenile Court is the way in which opposing counsel have

recognized the critical importance of maintaining respect and communication for the mutual

benefit of our clients and ourselves. We can be adversaries without being needlessly

adversarial -- and never personal. With apologies to Ecclesiastes and the Byrds, there is a

time for drawing lines in the sand but, more often, there is a time for honest efforts to seek

mutually beneficial solutions.

The local AG’s office is at 3939 South Park Avenue, Suite 180, Tucson, AZ 85714.

Their phone number is 294-6655.

Parent’s Attorneys

Each parent in a dependency proceeding is entitled to and receives separate

counsel. Often, at first blush, both parents look like they have identical legal interests. After

all, they have been raising the child together. However, the potential for conflicts of interest

is always present. One parent might be dealing with a drug problem where the other is in

denial. There might be some domestic violence in the household. One parent might be

cooperative with the Court and the other defiant. As a result, the Court routinely assigns

separate attorneys to avoid conflict problems down the road.

Most of the parent’s attorneys are assigned directly by the court. These attorneys

have a contract with the Court whereby they get paid a prearranged flat fee per case. All of

the parent’s attorneys have to pass a minimum training and are required to maintain

continuing legal education with the Court as well. Parents may be assessed a fee to offset

the costs of their lawyer. There is a list of parent’s attorneys and their addresses and phone

numbers in the course materials.

The primary role of the parent’s attorneys is to advocate for their clients in court. A

good parent’s attorney, however, will perform many non-litigation functions to assist the

26

parent in navigating the case plan process. A good parent’s attorney will help the parent

understand the child protection process and negotiate visitation; advocate for appropriate

services for the parent; advise the parent on the choices that will most likely result in return

of the child; and assist the parents to carry out their case plan tasks.

Sometimes being a good parent’s attorney means delivering bad news or advice that

the client does not want to hear [“No, having a six pack each night is not a good idea.”].

Parent’s attorneys often have to deal with clients in denial or who are high or who are

mentally ill. It is not an easy job but it is an important one.

Guardian Ad Litem

A Guardian Ad Litem (GAL) is an attorney appointed by the Court to advocate for the

client’s best interests (as opposed to the client’s stated legal objectives). Therefore, unlike

an attorney appointed to represent a party as an attorney, the GAL’s functions

independently of the client’s wishes and reports directly to the Court regarding the client’s

best interests.

A GAL is appointed whenever the court determines that the client (whether adult or

child) is not capable of making decisions in his or her own best interests and needs

protection. A GAL might be appointed where the client is too young, is under a mental or

psychiatric disability, is incapacitated, or chooses a position that the client’s attorney [or

perhaps others] feels is dangerous to the client. We will often act as GAL’s when our clients

are too young to understand the process. The Court may appoint GAL’s for parents who

have some condition that impairs their ability to protect their own legal interests.

Court Appointed Special Advocate (CASA)

The CASA is usually a non-lawyer who provides the Court with reports concerning

the best interests of a child. The CASA is a volunteer specially trained to spend time with

children, to get to know them, and to gather information for the Court. CASA is an

independent program administered by the Arizona Supreme Court. CASA’s are given wide

authority to access police files, hospital records, and even sealed court records. Unlike an

attorney/GAL, CASA’s cannot question or cross examine witnesses in court. They can,

however, provide extensive information that would not otherwise be available to the Judge

and may testify in court.

29

29

See ARS 8-522 for a listing of CASA authority and responsibilities

27

The Role of the Child’s Lawyer

In Arizona there are two types of lawyers for children in dependency proceedings:

attorneys

30

and guardians ad litem. The essential difference between the two is that an

attorney for a child attempts to maintain a normal lawyer-client relationship with the child.

By “normal” lawyer-client relationship, we mean that, as with all attorney-client relationships,

the child-client sets the basic goals while the attorney is responsible for carrying out those

goals. The attorney keeps the clients secrets and confidences, advises the client on the

best course of action, keeps the client reasonably informed of what is happening and owes

his or her primary loyalty to the client.

On the other hand, the Guardian Ad Litem reports directly to the court and advocates

for what the Guardian perceives to be the child’s best interests irrespective of the child’s

stated wishes. There is no attorney client relationship. Nor is there any obligation to keep

the client’s secrets and confidences.

31

WHEN IS AN ATTORNEY AN ATTORNEY AND WHEN IS AN ATTORNEY A GAL?

First a little background music.

The federal Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) requires the

appointment of a “guardian ad litem” “to represent the child” in abuse or neglect

proceedings.

32

CAPTA allows that the representative may be “an attorney or a court

appointed special advocate.” But CAPTA does specify precisely what “represent the child”

means. May the CAPTA-GAL act as a traditional client-directed counsel? Is the

GALsomething more like a “best interests” attorney? Or may the GAL be something else?

CAPTA itself does not offer an answer. Instead, the Act says that the purposes of the

guardian ad litem are

(I) to obtain first-hand, a clear understanding of the situation and needs of

the child;

and

30

In Arizona statutes and rules referring to Juvenile Court, the term “attorney” is used

interchangeably with the term “counsel”

31

See AZ Ethics Opinion 2000-6, September, 2000.

32

See 42 U.S.C. § 5106a(b)(2)(A)(xiii) (2000), which requires states to have “provisions and

procedures in every case involving an abused or neglected child which results in a judicial

proceeding, a guardian ad litem, who has received training appropriate to the role, and who may be an

attorney or a court appointed special advocate who has received training appropriate to that role (or

both), shall be appointed to represent the child in such proceedings–(I) to obtain first-hand, a clear

understanding of the situation and needs of the child; and (II) to make recommendations to the court

concerning the best interests of the child.”

28

(II) to make recommendations to the court concerning the best interests of

the child.

33

The “best interests” language does not sound as though the GAL can be a traditional

client-directed attorney. Nonetheless, many places, including Pima Count Arizona,

recognize that that appointing a client-directed attorney satisfies the CAPTA-GAL

requirement:

“because advocating the child’s wishes and preference could be seen as in the

child’s best interests, serving the child’s best interests, and helping the court to better

arrive at overall decisions that are best for the child.”

34

The Arizona statute is similar but not exactly the same as CAPTA. ARS § 8-221 (I)

requires that

In all juvenile court proceedings in which the dependency petition includes an

allegation that the juvenile is abused or neglected, the court shall appoint a guardian

ad litem to protect the juvenile's best interests. This guardian may be an attorney or a

court appointed special advocate.

35

There is a little disconnect between 8-221 and actual practice. First, courts in

Arizona appoint either a GAL or an attorney irrespective of whether or not there is an

allegation of ”abuse and neglect.” Dependency can result from circumstances where there

is no abuse or neglect – such AZ courts routinely appoint representatives for children in all

cases.

In addition, Rule 40 of the Rules of Procedure for Juvenile Court allows the Court to

appoint a GAL “to protect the interest of the child.”

36

Rule 40.1 impliedly authorizes the

appointment of attorneys for children. Rule 40.1 also sets out the responsibilities of both.

37

These new rules set out some basic standards – meet with child clients before hearings,

attend trainings, explain the attorney or GAL role to the child in a developmentally

appropriate manner.

In Pima County, the Court has chosen to appoint only attorneys as GAL’s – no lay

people.

38

Pima County has also chosen to distinguish between attorneys appointed to

33

See, e.g., Ala. Code § 12-15-102 (2013) Guardian ad litem is a “licensed attorney appointed by a

juvenile court to protect the best interests of an individual without being bound by the expressed

wishes of that individual.”

34

See Guidelines for Public Policy and State Legislation Governing Permanence for Children, U.S.

Dept.of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children Youth and Families, 2002 found at

http://archive.org/stream/guidelinesforpub00duqu/guidelinesforpub00duqu_djvu.txt

35

ARS § 8-221(I)

36

Rule 40, Rules of Procedure for the Juvenile Court

37

Rule 40.1, Rules of Procedure for the Juvenile Court

29

represent a child as “counsel” and those appointed to represent a child as GAL. This

distinction appears to be authorized by ARS § 8- 824(B)(3) which mandates the presence of

the child’s “guardian ad litem or attorney” at the preliminary protective hearing.

39

When is an attorney a Guardian Ad Litem and when is an attorney a Lawyer?

In Pima County, the default position is that we are a child’s attorney and not the GAL.

In Maricopa County, it is the opposite. Confusing? Wait, we’ve got more.

In Pima County, by local court policy, the Juvenile Court appoints an attorney for

each child in a dependency proceeding.

40

Thus, when the Clinic represents children, unless

specifically directed by the Court, our default position is that we act as the attorneys for

our child-clients.

In addition, pursuant to another local rule, we follow the American Bar Association

Standards of Practice for Lawyers Representing a Child in Abuse and Neglect Cases.

41

The ABA standards distinguish a client-directed lawyer [“child’s attorney”] from a

GAL. The ABA standards define a child’s attorney as:

38

Although Rule 40 above contemplates that the GAL be either an attorney or lay person, new Rule

40.1 [Duties and Responsibilities of Appointed Counsel and Guardians Ad Litem] seems to

imply that GAL’s need to be attorneys statewide. Rule 40.1 Rules of Procedure for Juvenile Court.

39

ARS § 8- 824(B)(3)

40

GALs are not routinely appointed but may be appointed where circumstances warrant. We will

discuss those circumstances a little more fully below.

41

ABA Standard A-1. These standards can be found at the ABA web site at:

http://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/administrative/child_law/repstandwhole.authche

ckdam.pdf There is not universal agreement about the role of a child’s lawyer and the ABA

standards are not the only ones. We will explore some of the other standards in class during the

semester.

30

The term "child's attorney" means a lawyer who provides legal services for a

child and who owes the same duties of undivided loyalty, confidentiality, and

competent representation to the child as is due an adult client.

The ABA standards define a GAL as follows:

A lawyer appointed as "guardian ad litem" for a child is an officer of the court

appointed to protect the child's interests without being bound by the child's

expressed preferences.

So, our default position is that we are client directed lawyers for children.

Here is what the ABA says:

These Standards explicitly recognize that the child is a separate individual with

potentially discrete and independent views. To ensure that the child’s independent

voice is heard, the child’s attorney must advocate the child’s articulated position.

Consequently, the child’s attorney owes traditional duties to the child as client

consistent with ER 1.14(a) of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct. In all but the

exceptional case, such as with a preverbal child, the child’s attorney will maintain this

traditional relationship with the child-client. As with any client, the child’s attorney may

counsel against the pursuit of a particular position sought by the child. The child’s

attorney should recognize that the child may be more susceptible to intimidation and

manipulation than some adult clients. Therefore, the child’s attorney should ensure

that the decision the child ultimately makes reflects his or her actual position.

42

That may work for a teenager. But how do you take direction from a 2 year old?

The ABA standards recognize that a very young or a pre-verbal child is unable to

direct a lawyer. Therefore, the ABA standards imply that these are situations – especially

for a very young child – where the attorney essentially acts as a Guardian ad Litem:

the Standards do not require the child's attorney to discuss with the child

issues for which it is not feasible to obtain the child's direction because of the

child's developmental limitations, as with an infant or preverbal child.

43

The short answer is that we do what we can to try and figure out what the

child’s position would be -- knowing what we know about the child. In other words, try

and figure out – from the child’s point of view – what the child’s legal interests are. It is a

pretty fine line between that and being a Guardian ad Litem where we simply advocate for

what we perceive to be the child’s best interests. And reasonable persons can and do

disagree. That’s one of the things that makes this work so interesting.

42

Standard A-1 Commentary

43

Standard B-4 Commentary 2

31

The ABA standards [and those of the Arizona State Bar] recognize that a court may

need to appoint a GAL when the attorney believes that the child’s age and/or level of

development impairs the child’s ability to comprehend what is happening and to make

informed and intelligent choices; and the often closely related situation where the attorney

believes that the child’s choices are not in the child’s best interests.

44

Both the ABA Standards and the State Bar Committee Opinion ask us to follow Rule

1.14 of the Model Rules of Professional Conduct [which is identical to Rule 1.14 of the

Arizona Rules of Professional Conduct]. Rule 1.14, as interpreted by both the ABA and

Arizona Committee, treats age like any other disability related to the client’s capacity to

make reasoned decisions. Essentially, we are asked to deal with the disability as best we

can while attempting to maintain as close to a lawyer-client relationship as possible.

45

Rule 1.14 also asks attorneys to make an independent determination of the client’s

capacity and requires lawyers to request that the court appoint a guardian [in this case, a

GAL] when the client is not capable of a reasoned decision.

46

The scope of the

guardianship should be related to the area in which the client is having difficulties. The

attorney would continue to advocate the client’s articulated position once the guardian is

appointed.

FYI, in Maricopa County, attorneys are appointed as child-directed advocates

only for older children – usually 12 and up. Otherwise, the Maricopa default position

is to appoint Guardian Ad Litem for all children.

What does the GAL do?